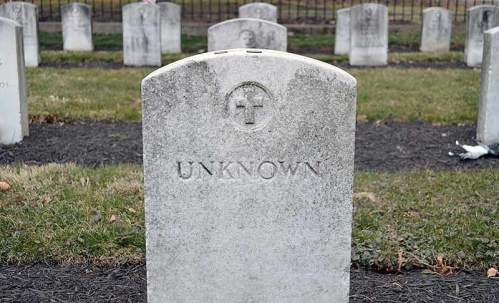

Miles Stead died from brain injury

Guest Commentary

Published May 15, 2016

Miles Stead, a two-year-old Lakota boy, was killed by

his foster mother just months after being taken from his home on the

Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota. His story should be raising alarms

about the rampant removal of Native American children from their

families in violation of federal law, yet it has been largely ignored by

the national media.

Stead’s foster mother, Mary Beth Jennewein, was

arrested in March and charged with second degree murder and four counts

of voluntary manslaughter. A hearing held May 11 denied Jennewein a

reduced bond. Her conviction is anticipated in June.

Nina Stead, Miles’s biological mother, had no

history of child abuse when her son was taken after she was found

drinking a beer. If the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) were adhered to,

Miles could have been saved, and this injustice could have been

prevented.

ICWA is meant to address the widespread separation of

Native American children from their families and tribes. Its purpose is

to protect the rights of children to live with their families, and to

promote the stability and security of Indian tribes and families. The

federal law dictates that placement preference for the child is to be

given to extended family or tribal families, and that tribes be notified

when their children are placed in the foster care system, which

provides the tribes a chance to intervene in state proceedings.

However, ICWA is constantly violated. Why? It’s

unfortunately simple. Native American children are seen as cash cows.

The Department of Social Services (DSS) categorizes Native American

children as “special needs,” which brings the state and adopting

families extra cash.

South Dakota for example, which is notorious for

its ICWA violations, reels in $79,000 per Native American child per

year, and families who adopt can claim a tax credit of $13,400. Seven

tribal governments endorsed a 2013 report concluding there is “a strong

financial incentive for state officials to take high numbers of Native

American foster children into custody.”

Native American children continue to be placed in

foster care at an alarming rate. They constitute two percent of the

total number of children in foster care, even though they only make up 1

percent of the United States child population. In South Dakota, more

than 750 Native American children are placed in foster care per year,

making up nearly one-third of the state’s foster care population,

despite only making up 13 percent of the total child population.

ICWA violations have led to almost 90 percent of

Native American children being placed in non-Native homes. These

children hold the future of their tribe, they are the source of

revitalization for tribal communities and their continued removal places

tribes at risk of becoming extinct. If children continue to be taken at

the current rate there may not be children to continue the tribe, and

the cultural identity of the tribe can’t be passed down.

There have been developments in the past year however,

suggesting that this trend of unbridled ICWA violations may finally

begin slowing down. Last year, the Bureau of Indian Affairs published

new ICWA guidelines to strengthen the law and ensure its compliance, and

that same year the courts found that South Dakota willfully violated

ICWA. Officials within the DSS, the state attorney and Judge Jeff Davis

were found to have violated ICWA. Their actions resulted in thousands of

children being placed with non-Native families.

What’s more, the Administration for Children and

Families proposed in [month] to record ICWA-related data, which has

never been done before and is expected to illuminate the extent of

overrepresentation of Native American children in foster care. Last

month, a Memorandum of Understanding was announced between the BIA,

Department of Justice and Health and Human Services to ensure ICWA

fulfills its intended purpose.

State ICWA noncompliance has spun out of control, and

at long last U.S. government agencies have become aware of what Indian

Country has known for decades — that children like Miles succeed better

when raised by their families. For people like Susan Becker, a close

family friend of Miles’ mother who is much too familiar with seeing

Lakota youth taken from their families, this level of attention is long

overdue.

“ICWA needs to step in earlier,” said Becker, a member

of the Rosebud Reservation. “My nephew was murdered because a woman

wanted to collect a paycheck.”

Becker had known Miles since he was born, and views

his mother as family, she refers to Miles as her nephew and had

temporary guardianship status prior to his removal. As soon as Miles was

taken from his mother, Becker sprung into action and attempted to gain

custody of him. However, since she is not a blood relative, the DSS said

she’d have to take a foster parent class, which they only offered to

her in March.

“Miles passed away before I could even start the

classes,” Becker said, adding that the DSS agents made the process very

difficult for her.

As per ICWA’s guidelines, Miles should have had

preferential placement with a tribal member or family member, but the

DSS quickly placed him in a non-Native home.

Coroners found Miles with a fractured skull and

internal bleeding. They ruled traumatic brain injury as the cause of

death. Jennewein told law enforcement that Miles was “known to hit his

head a lot,” suggesting that this happened while at daycare, but

surveillance video from the daycare proved this was not the case.

Miles’ story is a testament that adherence to ICWA can

literally be a matter of life and death. Children are being removed

from their families for preposterous reasons that one could not imagine

happening to a White family.

“I don’t know how to put this, but if you’re drinking

one beer and someone calls the police you’ll get your kids taken,”

Becker said. “The state’s making money off our children.”

This issue plaguing Indian Country demands the

attention of the masses. Native American issues cannot continue to be

placed on the backburner and ignored by popular media.

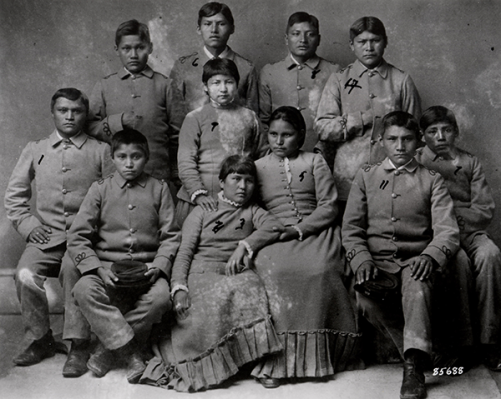

The Lakota People’s Law Project is calling for a Truth

and Reconciliation Commission to provide recommendations to Congress on

how to develope child and family service programs that are run by

tribal nations, for tribal nations. This commission would take testimony

from boarding school survivors, identifying how the boarding school

system impacted their lives so that their stories will not be lost in

U.S. history. It would also conduct comprehensive national studies

focused on the past and ongoing effects of the boarding school policy,

and advise Congress on ways to begin an official process of healing.

Acquiescing to the DSS’ widespread seizure of Native

American children will lead to the eventual dissolution and destruction

of tribes. Our children are our future. Our children are sacred.

Ardy Raghian is the press director for the Lakota People’s Law Project.