Oglala children, Native boarding school victims laid to rest in weekend-long ceremony

The remains of three Oglala Lakota students who died while attending the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in the 1890s were returned home this month and reburied in their South Dakota homelands

OGLALA, S.D. — As darkness descended, the procession to rebury Samuel Flying Horse (also known as Tasunke Kinyela) made its way along a dirt road to the Brave Blue Horse Family Cemetery outside of Oglala, S.D., on Sunday, Sept. 22. The memorial service and community gathering had run behind schedule and now the blue skies that marked the day and golden light of the setting sun were gone.

Samuel died as a student at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School and waited 131 years to be disinterred and returned to his homeland. Those gathered were not about to let darkness make him wait longer.

Approximately 20 vehicles in an open field encircled and directed their headlights on the small fenced-in cemetery. The pounding of the drum, the singing of songs, and prayers drifted up as pinpoints of starlight began dotting the night sky. Eventually, a group of men lowered Samuel’s casket, covered in a star quilt and a bouquet of red roses, into the ground. Samuel was now part of the land he had left behind in 1891.

Along with Fannie Charging Shield and James Cornman, Sameul was reburied on the Pine Ridge Reservation this past weekend. Fannie and James were buried at St. Julius Cemetery in Porcupine on Saturday, following a community gathering at the Pahin Sinte Owayawa School to celebrate the homecoming of the three Oglala Lakota students. Samuel was reburied the following day.

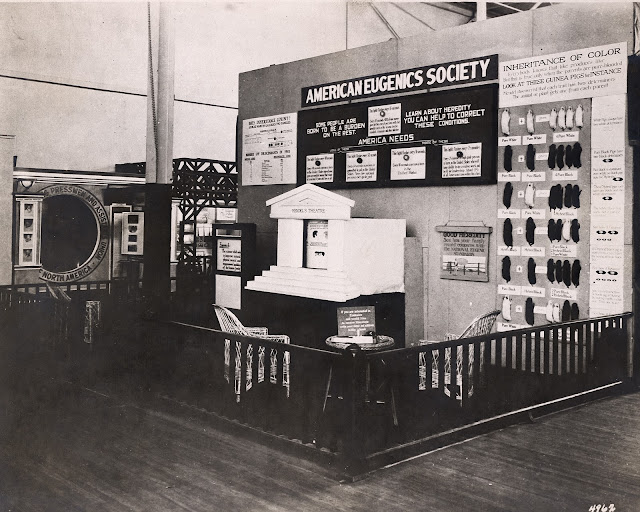

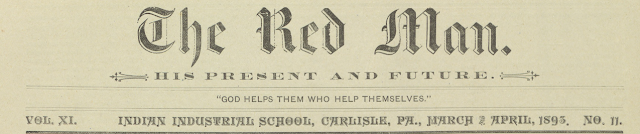

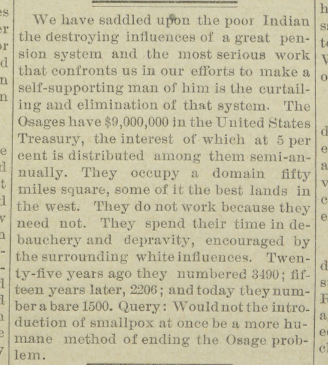

They died in the early 1890s as students of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, the first federally run, off-reservation boarding school for Native Americans. Approximately 8,000 Native American students attended the school in a misguided attempt at forceful assimilation into white civilization by cutting all links in their cultural chain. It became the model for more than 400 schools across 37 states and territories in the U.S. and provided a blueprint for Canada’s notorious residential school system.

The three students were among the estimated 232 students who died during its years of operation from 1879 to 1918. Each passed from tuberculosis, then called consumption. It was the leading cause of death at the Carlisle school.

The dream

It wasn’t until the three students came home to Pine Ridge a week earlier that Corrine Brave, 70, checked her family tree and realized she was a relative of Samuel Flying Horse, who school records indicate was an orphan. With some trepidation, she stepped forward to claim Samuel and offer a burial site.

As the mourners gathered, illuminated by the headlights of the surrounding cars, Corrine Brave told the gathering the story of a dream she had had the night before. A figure of a man descended a steep series of steps toward her. He kept slipping and falling, appearing to be legless. She could not make out the features of his face, but his voice was distinct. As he got closer, he said “wopilayelo” (the male version of thank you) to her four times. She felt the man was Samuel.

The dream woke her.

“I sat straight up, looked around thinking I was hearing things,” she recalled. “Then I said to myself, ‘Thank you. Thank you.’ … So that's when I knew I was doing the right thing for my relative,” Brave said.

“It was for love – the love of my relatives, the love of my family. … I just really felt that in my heart that there was a relationship between us.” She began to think of herself in the role of an auntie.

He was buried beside his namesake, her late brother Samuel Brave.

The 'peaceful war'

The weekend’s ceremonies started Saturday morning when a convoy of nearly 25 cars made their way from Pine Ridge through the rolling hills. It traveled along the Chief Bigfoot Highway past the Wounded Knee Massacre site. It was a morning to celebrate and memorialize the three students.

Fannie, James and Samuel left home for Carlisle in the name of education. The students did not realize they were taking part in a “peaceful war,” one fought in the classroom using education as the ammunition to force assimilation and cultural destruction. Books and blackboards were deemed a cheaper solution to “the Indian problem” than bullets and battlefields.

The school, located on a vacant U.S. Army base in Pennsylvania, was run in a military fashion. It was only fitting that upon their return they be memorialized in a school, Pahin Sinte Owayawa, in Porcupine, S.D.

It was the graduation day they had not lived to see.

The three caskets were carried into the school gym and placed in ceremonial tipis. About 100 community members and students sat in folding chairs and bleachers. They gathered to gain knowledge from all the students had endured over a century before by traversing 1,500 miles across the country to a school that had all intentions of erasing their culture. The trio of students and their experiences had become the teachers. Courage, perseverance and overcoming adversity were their subjects. It was their time to be honored.

“They were innocent, and they were raised right. And when they went to Carlisle, their parents got them ready,” Pat Janis, a medicine man and relative of Fannie Charging Shield, had said the previous day in an interview with ICT. “They said, ‘This is a different way than we live, but you got to go forward. You got to learn these things. This is the way we're going to live now. So you got to have strength. You got to have courage and do your best. Get educated. You're going to help us.’ So they prepared them. Although those students didn't want to go there … they took it as a warrior. … They said, ‘I'm scared. I don't know what this is, but my parents believe in me, and they want me to move forward into this way of life. I'm not selling out our people.’”

A question becomes a movement

The movement to repatriate the remains of students from the Carlisle cemetery began in 2015, when the Sicangu Youth Council of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe stopped at Carlisle following an youth event in Washington, D.C. It began with the simple question no one had thought to ask in earnest before, “Why aren’t we doing something to bring them home?”

The question ultimately led the Office of Army Cemeteries to begin the process of returning students’ remains to their tribal communities. Since 2017, the Office of Army Cemeteries – which oversees the Carlisle cemetery along with other military gravesites, including Arlington Cemetery – has disinterred and returned the remains of 32 children from the school’s cemetery. Still, 146 students have yet to be returned to their tribes prior to this fall’s disinterment.

Three former members of the Sicangu Youth Council, Chris Eagle Bear, Rachel Janis, and Jayden Whiting, were recognized and honored at the memorial service for initiating the return of Carlisle students.

“You know, 10 years later, I didn't expect to be where we are today. Because at the end of the day, we were just kids with a curious question,” said Chris Eagle Bear, 26, who is currently a Rosebud Sioux Tribe councilman.

“My generation is the first generation that is not a part of the boarding school era. And with that, we're able to share what we feel. We're able to speak on matters that a lot of our people couldn't speak on for a long time because they were scared,” Eagle Bear said. “The older generation started sharing their stories, started sharing things that they've never shared before with anyone.”

Janis called the relatives of the three students forward for a ceremony of healing and compassion near the end of the event.

“We are still in mourning over it. It's a good thing that we can get over it now, because sometimes we walk around with sadness and mourning, and we don't even know we're in mourning ’til we get a physical sickness like diabetes,” he said.

For Justin Pourier, the Oglala Sioux Tribal Historical Preservation Officer, who had gone to Carlisle and accompanied them on their homecoming, there was the satisfaction of a mission accomplished. He often thought of all they had endured and felt a love and an attachment to the three students.

Yet, there was so much more work to be done. Pourier thought about other Oglala Lakota children who remain buried at other boarding school cemeteries and artifacts in the possession of museums and academic institutions. He spoke at the event of the Oglala Lakota students buried at the White’s Indiana Manual Labor Institute, a Quaker-run, Native American residential school in Wabash, Ind.,which was initially established by Quaker missionaries in 1862. And he talked about his hope to continue to have artifacts, such as war bonnets and moccasins with beautiful beadwork, returned from various museums to a place where Native youths could draw inspiration and pride in the beautiful craftsmanship.

“If they can see all these things, it reestablishes their pride and their sense of knowing who they are. I’m hoping it brings healing, and helps our children grow back into the strong nation we used to be,” Pourier had said while in Carlisle. “We can't afford to send a busload of kids all the way to New York to look at something that should be back home.”

As the morning of speeches and prayers came to a close Saturday, Michael Littlevoice, a Ponca and Omaha man living in Ponca City, Okla., asked permission to address the crowd. He had attended Chilocco Indian Agricultural School with Orville Flying Horse of McIntosh, S.D., in the early 1970s. He felt compelled to attend the two events to help the community heal and celebrate.

He performed an original composition on his flute inspired by the occasion. The haunting yet peaceful music echoed through the room, setting the mood for the reburial that would follow shortly, the ending to the long and unfortunate journey home of Fannie, Samuel and James. While he performed as an instrumental, he informed those gathered of the words:

“After all of these years, I'm home, I'm home. I'm home after all these years.”

This story was originally published on ICTNews.org.

https://www.grandforksherald.com/news/south-dakota/oglala-children-native-boarding-school-victims-laid-to-rest-in-weekend-long-ceremony

______________________________________________________

This story was written by one of our partner news agencies. Forum Communications Company uses content from agencies such as Reuters, Kaiser Health News, Tribune News Service and others to provide a wider range of news to our readers. Learn more about the news services FCC uses here.