A Sixties Scoop survivor who wrote an autobiography about her experience hopes that sharing her story will not only raise awareness but perhaps also embolden others with similar life experiences to embark on their own personal path of healing.

Shirleylee Shields, who moved to Sundre about a year ago, was taken away from her biological parents at the age of three and subsequently placed into the care of a foster family in a strict religious sect.

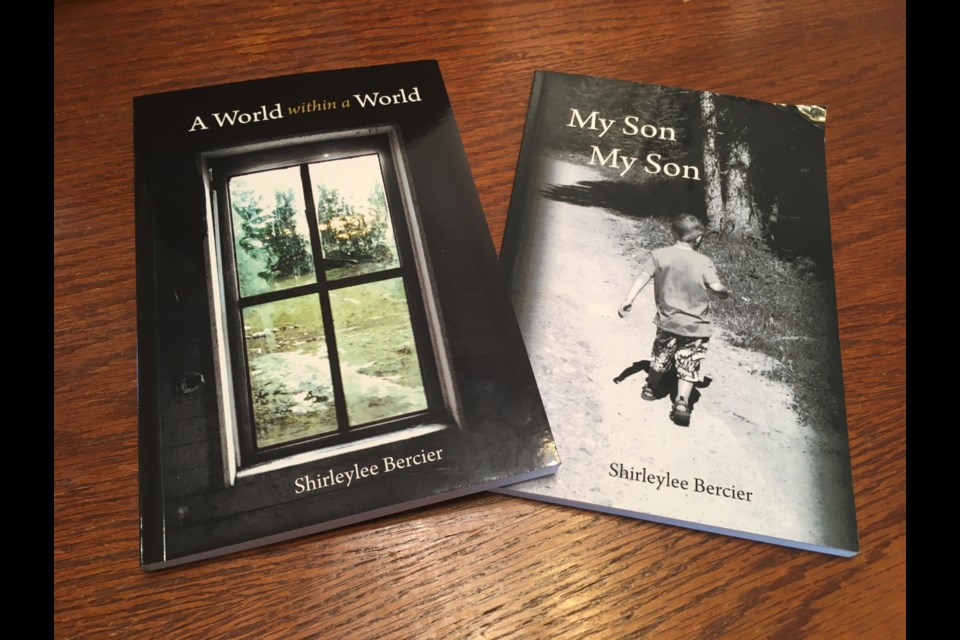

She recently offered a presentation at the Sundre Municipal Library to provide insight into her 2009 book, A World Within A World. She also penned a sequel called My Son My Son.

During a June 13 interview with the Albertan, the 58-year-old candidly recounted the long, difficult journey of self-discovery that ultimately led her to walk away from a fundamentalist life that was forced upon her and to reconnect with her family and heritage.

Sharing experience a liberating step

“There’s no more skeletons in the closet,” she said with a laugh in response to being asked how seeing her published story felt. “You have nothing to hide. It was the most freeing, cleansing thing to do, was to reveal and to bring all of this out and throw it on the table.”

At first, she confessed being “petrified” that nobody would even want to read her story. But A World Within A World is now on its fourth print run, while copies of My Son My Son are out of stock for now.

Born on May 1, 1965 in Benito – a small, rural Manitoba community just east of the border with Saskatchewan – Shields lived only briefly for three years with her six other biological siblings and parents, an English mom named Myrtle Harrington and a Métis dad called Herman Moses Bercier, at a home in the Roblin area south of where she was born.

“Me and my younger brother had been removed from the home and put into foster care and dad didn’t even know anything about it,” she said. “He came home (from working in the bush) and we were gone.”

Shields was fostered into a family that already had 10 children – making her a distant 11th – not far away from Roblin in a relatively remote rural community called Shortdale, Man., where her adoptive parents owned and worked a farm.

“They were part of the Mennonite society, but they were the Holdeman sector, which is the strictest of the Mennonite society,” she said. “There was no radio, no television, no higher education, no makeup, no jewelry; the list is endless. That’s where they dropped me off when I was three.

“It was all I knew, from three years old. You grow up with that environment, it’s just like a cult,” she said. “That’s why my book is called A World Within A World.”

Raised by her foster parents Benjamin and Tina Isaac, the couple eventually adopted her at age 10; a decision she would not find out until years later was actually Benjamin’s idea.

Strict religious upbringing

Amid a strict religious upbringing that demanded unquestioning conformity to rigid rules, Benjamin was among the few silver linings to be found.

“Even though he was a staunch believer and a member of the Holdeman Mennonite society – he loved me,” she said. “He is the only human that I knew growing up that loved me unconditionally; I did everything with my dad. He never hit me; he was the kindest soul that you could imagine.”

He even seemed to understand the internal struggle she faced on a daily basis.

“He knew,” she said. “Even when I was young – six or seven – I would look at him and I’d say, ‘I don’t belong here.’ And he’d say, ‘Well, for now, you do.’”

Expressing a deep respect born of affection for her adoptive father, she said, “I loved him and he loved me.”

Sometimes, she said he was even reprimanded.

“He’d be (temporarily) expelled from the church for associating with what they considered ‘worldly’ people; so, people of the town,” she said. “It blows your mind at the mentality that they are allowed to sit in judgment of every human being on this planet, but yet they will preach god’s love or whatever they want to believe Sunday morning. I mean, it’s just ludicrous.”

Yet she never developed a connection or relationship with Tina, who died in a vehicle collision in which only Benjamin and Shields survived; she was 15 at the time and subsequently sent away to live in Steinbach, Man. for 11 years.

But she does remember Tina as a “phenomenal gardener” who knew how to prepare a hearty meal.

“We were never hungry; we ate very well,” she said.

Pursuing her own path

Shields remained a part of that family until she decided to walk away from the strict sect in 1994 at about age 28. Although she had previously attempted to leave during a rebellious adolescent phase in her late teens, Shields said she “went back to the church because I didn’t know where any of my biological family was.”

Not having an identity to anchor to made forging out on her own path forward that much harder.

“When you grow up in that environment, they so masterfully indoctrinate you that you are worth nothing unless you are part of them,” said Shields, adding she was eventually forced into an arranged marriage with a member of the Holdeman Mennonites with whom she had four children.

“I had maybe spoken three words to him before we were engaged; if that,” she said. “And then we were married two weeks later; didn’t know him from Adam – didn’t know anything about him.”

She and her arranged husband eventually moved with their four kids to Rimbey from Kleefeld, Man. where they’d worked a dairy operation until 1993, and the writing on the wall became increasingly clear.

“There was a new little congregation starting there of the Holdeman Mennonites,” she said, referring to Rimbey. “And I knew that I needed to leave; I did not want to bring my children up in that environment.”

By the following spring, Shields had mustered up the courage to pursue her own path.

But the next leg in her journey was no walk in the park and involved a drawn-out legal battle to gain not only her freedom but also custody of her children.

“The church took my children because in their eyes I was going to hell, and if I had my children they would be going to hell with me,” she said. “So, I was probably fighting for two years to get my children back.”

Reconnecting with roots

In 1997, the fruits of her labour blossomed.

“I am the first woman in Canada and the United States to have taken this society to the Court of Queen’s Bench in Edmonton and I won my freedom,” she said, adding she was also granted sole custody of her children, who are now all adults and remain in close contact.

Now removed from the sect for more than 30 years, Shields said she decided to cut all ties after Benjamin died and has since been living her best life, eventually going on to remarry and have another daughter with Dave Shields, who had established a respectable reputation as a Calgary Stampede chute boss.

“My book is (about) my fight for freedom,” she said, adding it’s also about her journey of personal and spiritual liberation as well as rebuilding a relationship with her biological family and reconnecting with the Métis heritage that had been all but taken away from her.

“My biological family lived half an hour to an hour away from me my whole life, and I did not know that,” she said.

“My world was so hidden,” she said, adding that in 1979, the church pulled all of the Holdeman children out of the public school system and started their own private school system.

“So, we had nothing to do with the outside world,” she said.

“It was very healing for me to be able to let go of all these memories and this way of life and this programming; to put it all out there,” she said. “Because it took me 10 years to de-program. It’s like the MKUltra; it’s so brainwashing. Your value is based on what they say, not who you are.”

It wasn’t until the age of 24 while attending an uncle’s funeral that Shields finally met her biological father.

“It was so surreal for me because he stood there and he had these tears running down his cheeks and he just said, ‘You were only three when they took you; I never saw you again.’”

She recalls embracing him and offering him words of comfort and told him, “Well, I’m here now.”

Despite all of the time they were denied, Shields was nevertheless grateful to have the opportunity to get to know her father, who lived to be 90. Along the way, she was able to re-establish relationships with the rest of her biological family.

Sixties Scoop a stain on Canada’s history

Although she’s worked through her past trauma and since moved on, Shields remains committed to sharing her story of putting back together a life that was wrongfully torn asunder.

“That is one of the biggest injustices done in humanity, is removing children improperly,” she said.

Calling the Sixties Scoop a “horrific” stain on Canada’s history, Shields said there to this day remains plenty of room for improvement on the path to meaningful reconciliation.

“Everybody wants to talk about reconciliation with dollar signs,” she said.

But all of the money in the world won’t make much difference if survivors’ stories are downplayed – or worse, ignored – and their lives are not valued enough to reach out and listen to their experiences, she said.

Asked for her response to people who downplay what happened or who say it’s in the distant past and that it’s time to move on, she said, “Well they definitely – Number 1 – haven’t lived it. You don’t forget it.

“I’ve had a lot of people say, ‘Well, at least you had a good life.’ You mean, at least I was given air and water and a house and food? Sure. I was given the necessities of life, absolutely,” she said, adding bluntly, “but we cannot move forward as a society – as a nation – until we are ready to listen and to heal.”

Recognizing history part of reconciliation

Dismissing history without acknowledging it and addressing the harm it caused serves only to perpetuate the cycle, she said.

“There’s many things that are in the past. But they are not cleaned up, so they are constantly coming forward,” she said.

“My journey has been bringing in awareness that this still is happening,” she said, adding the fundamentalist community she was raised in hasn’t changed and that Indigenous children are still being taken away from their families by social services.

“My book is still relevant because what is in my book is still happening today,” she said. “So if people say, ‘I don’t understand, that happened in the past, why won’t you let it go?’ – I have let it go, but I’m still bringing awareness that this is still going on today.”

For those who might struggle to relate or understand, Shields encourages them to consider how drastically their own identity would be impacted faced with the sudden loss of a loved one; a formative life experience that causes a tremendous sense of loss and grief as those left behind try to put their life’s shattered pieces back together.

Money alone can't remedy past injustice

Healing is arguably the most important part of the path to reconciliation, she says, but it can also be among the most difficult for all too many survivors.

Shields, who enjoys every opportunity to speak publicly about her experience, says she’s been in rooms with dozens of survivors who were either too terrified or ashamed to share their own stories because they don’t feel valued as that’s how they’ve been treated. Fear, she added, can be an incredibly powerful emotion that prevents people from opening up.

But Shields enjoys a heart-to-heart conversation and helping others start or continue along their own paths of healing, which goes further toward mending past wounds than money alone ever could.

“We have stepped so far away from giving a damn because it’s easier to throw dollars at people,” she said.

“(But) the possibilities are endless when it comes to learning and understanding who you are, and I think it just comes back to empowering yourself and seeking your personal freedom and truth because nobody can give that to you except yourself.”