Inside the fight for Indigenous jurisdiction over child services in Canada

By Tracy Sherlock

Jan 23, 2025

Content note: This story mentions residential schools in Canada

Indigenous Peoples are reclaiming their right to take care of their children after at least 500 years of colonization.

The transition to taking back

jurisdiction — the power to make legal decisions — over their children

is a move full of hope, but also fraught with concerns about inadequate

funding and offloading responsibility from federal and provincial

governments to Indigenous nations.

“The reason [children are a top

priority for First Nations people] is that children are the keepers of

the possible. They’re the keepers of our tradition. They’re the keepers

of our peoples,” said Cindy Blackstock, a noted activist for Indigenous

children’s rights who is a member of the Gitksan First Nation and

executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society

of Canada.

“If you don’t pay attention to the

children, then really, you’re losing that. You’re losing your culture,

you’re losing everything.”

Children grow up into parents and grandparents, she noted.

“There’s an understanding that you

have to treat them well, because… everything that happens to them will

ripple forward to generations that we’ll never know,” Blackstock said.

“We have a responsibility to put

them first. They are even more important than the Elders. The Elders are

important because they teach the children, but the children are the

most important.”

Indigenous people ‘know the best for their children’

Colonization continues to strongly influence the landscape of child services in British Columbia and has for generations.

For at least 500 years,

Indigenous Peoples in the land now known as Canada have been fighting

racist approaches and policies imposed through colonization, as reported in 2015 by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

The Indigenous Peoples of this land,

over centuries, lost their children to colonial, assimilationist

practices like residential schools, day schools and boarding schools,

the ‘60s Scoop and more recently, the so-called child welfare system.

Jessica Knutson, who was involved in the system growing up, has been working as a social worker for the past six years.

Knutson, 30, is also part of the National Council of Youth in Care Advocates,

a group that advocates for greater and more equitable support for youth

in and aging out of care. Her grandmother was Cree, from Treaty 4

territory in Saskatchewan.

Knutson says Indigenous jurisdiction

over children should never have been in question and the history caused

harm to Indigenous Peoples that will take decades to remedy.

“Indigenous people across the country

and across the world have always talked about how they know the best

for their children, and they do,” Knutson said.

“The hundreds of years of

attempted genocide of Indigenous Peoples here has definitely impacted

the ability to do that, but it’s amazing the work that communities are

doing, even without the monetary and other support that they should be

getting from the federal government.”

At least 4,100 Indigenous children died or went missing in residential schools, which the TRC called a cultural genocide.

Conditions were horrific,

including physical and sexual abuse, unsanitary living spaces causing

rapid spread of diseases, and inadequate food causing malnutrition. The

children were removed from their parents and their cultures and they

were not allowed to speak their own language at the schools.

Although residential schools were

phased out by the late 1990s, Indigenous children are still being

removed from their homes. The ‘60s Scoop saw an increase in the number

of Indigenous children put into government care, a practice that

continues today.

Check out Spotlight: Child Welfare

The intergenerational trauma of

divided families contributes to a vast overrepresentation of Indigenous

children placed in government care.

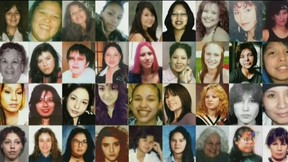

It also contributes to the high rates

of disappearances, murders and violence experienced by Indigenous

women, as reported by the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.

Traditionally, Indigenous Peoples saw

the care of a child as the responsibility of an extended family. When

problems arose, the extended family would come together to support the

child and try to come to a consensus decision to solve the problem, the

1992 report Liberating our Children says.

The colonial way — separating children from their parents — was different and harsh.

“Your child protection laws have devastated our cultures and our family life. This must come to an end,” the 1992 report said

‘You have to do something different’

Today in British Columbia, 67.5 per cent of children in government care are Indigenous, while Indigenous people only make up 5.9 per cent of the overall population.

The Canadian 2016 Census found that Indigenous children represent more than half of children in government care in Canada, despite accounting for only 7.7 per cent of the overall population of children.

Blackstock won a landmark

decision at the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal in 2016, which found that

the federal government discriminated against First Nations children

living on reserves, particularly in terms of funding.

“A First Nations child is 17 times

more likely to be removed from their family than a non-Indigenous child

is, and it’s due to those factors at the ground, the poverty, the poor

housing, the multigenerational trauma, the addiction, domestic violence,

those are the drivers,” Blackstock said.

The TRC, which is approaching its 10-year anniversary and whose leader, Murray Sinclair, died in November 2024, released the TRC’s 2015 Calls to Action that start with five child recommendations for improving child services in Canada.

Those include a call for child

welfare legislation to “affirm the right of Aboriginal governments to

establish and maintain their own child-welfare agencies.”

Poor outcomes for children raised in

foster care are the reason change is needed, said Jennifer Charlesworth,

B.C.’s representative for children and youth.

Charlesworth, who is not Indigenous, has been in the role since

2018. Her office is mandated with advocating for children and youth,

monitoring services for them and conducting reviews and investigations

into critical injuries and deaths of children receiving government

services.

The primary reason for Indigenous

children being taken into government care is poverty and once they are

in care, their mental and physical health suffers, as does their

educational achievement and even their sense of hope for the future, she

said.

“Indigenous children spend more

time in care than non-Indigenous children. They are often disconnected

from their culture, from their family and community. We know that that

has an impact on their sense of belonging, and their sense of identity,”

Charlesworth said.

“When you see poor outcomes and the

perpetuation of harm, you have to do something different. Indigenous

people in their strength and resilience have advocated for changes in

their role in child welfare and are resuming their rightful place as

carers and protectors of their children.”

Jennifer Charlesworth (far right), B.C.’s representative for children and youth, presents the ‘Don’t Look Away’ report

on July 16, 2024. Onstage from left are Mary Teegee, Cheryl Casimer,

Grace Lore and Grand Chief Stewart Phillip of the Union of B.C. Indian

Chiefs. Photo submitted.

‘We need to take care of our own children’

The multigenerational trauma created

by colonialism, residential schools, the ‘60s Scoop and the

overrepresentation of Indigenous children in the child services system

is evident around us. It’s evident in the statistics that show the

overrepresentation of Indigenous people among the unhoused population,

among the deaths from poisoned drugs and in the criminal justice system.

“This is why it’s so important. We need to take care of our own children because the current system doesn’t work,” regional Chief Terry Teegee told more than 1,000 Indigenous leaders, Elders and caregivers who gathered in late October for the Our Children, Our Way conference in Vancouver.

In 2019, the federal government passed Bill C-92, An Act Respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis Children, Youth and Families, which affirmed jurisdiction over their children.

“When you get boiled right down to

it, for a person on the street, [jurisdiction] is the ability to make

decisions for your own kids,” Blackstock said.

Knutson says the return to Indigenous jurisdiction is needed.

“Children and women are the heart of

community,” she said. “It’s so important and really significant that

nations are able to use their own protocols to be able to care for their

children, because Indigenous nations need to be making the decisions

for their own children, and that looks different for each nation.”

As of Jan. 17, 2025, 86 Indigenous governing bodies representing over

110 Indigenous communities have submitted 66 notices to exercise

jurisdiction over child and family services, and 42 requests to enter

co-ordination agreement discussions pursuant to section 20 of the Act.

Twelve Indigenous child and family services have come into force, and

11 co-ordination agreements have been signed, according to Indigenous Services Canada.

Co-ordination agreements are

a transitional way to exercise jurisdiction over child services that

can include the Indigenous nation and the provincial government, each

having specific roles and responsibilities, with the best interest of

the child as the focus.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples also

recognizes the right of Indigenous families and communities to be

responsible for the upbringing and well-being of their children.

“Responsibilities

for raising children are core aspects of the right to self-government,”

said Hadley Friedland, an expert in Indigenous law and professor in the

faculty of law at the University of Alberta, at the Our Children, Our

Way conference.

“This is also obvious based on how the Crown attempted to destroy Indigenous families through assimilation policies.”

British Columbia introduced

its Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act in 2019,

establishing UNDRIP as the basis for provincial reconciliation. It also

amended its Child, Family and Community Service Act by passing Bill 38, which strengthens Indigenous community’s ability to resume authority over child and family services.

The first steps forward

In 2023, the Federal Court of Canada approved a $23.24-billion settlement to

compensate First Nations children and families who were harmed by

discriminatory underfunding of the First Nations Child and Family

Services program.

In addition, a 10-year,

$47.8-billion settlement agreement to reform First Nations Child and

Family services going forward was presented in July 2024.

The Assembly of First Nations Chiefs

rejected that deal in October, saying the funding was inadequate, the

governance structures lacked transparency and were not accountable to

First Nations, that it contained a weak dispute resolution process and

that committing to the settlement for 10 years would leave no way to

negotiate further, the organization Our Children, Our Way said in a news release.

“Our leaders have rejected this draft

agreement because they know what is at stake: our children. This was

not a good agreement: we have to do better for our children,” said Mary

Teegee, chair of the Our Children Our Way Society.

Blackstock said there were fundamental problems with the agreement Chiefs rejected.

“It wasn’t really a vote against, it

was a vote for good governance, stability and non-discrimination for

kids, and to make sure that Canada was held accountable to the legal

obligations it currently has to First Nations children,” Blackstock

said.

“That $47.8 billion was advertised as

being there, but under closer scrutiny, looking at the agreement, it

really was a one-year funding deal that gave Canada wide discretion on

the level of funding and the terms of funding over the next nine years.

After nine years, there was nothing for these kids, nothing was

guaranteed.”

There were also issues with governance in the rejected agreement, Blackstock said.

“The chiefs, if they had voted for

it, that would be the last decision they would make on their children

for nine years, on this funding approach, all of that would be ceded to a

secret committee that had extensive liability protection but no

accountability,” Blackstock said.

Nonetheless, Blackstock is hopeful for a better deal.

“This is a legal case. Canada has to

comply with that legal standard, stop discriminating and prevent it from

happening again,” Blackstock said.

Executive director of First

Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada Cindy Blackstock

speaks on child services during the Assembly of First Nations Special

Chiefs Assembly in Ottawa on Dec. 4, 2024. Photo by Spencer Colby, The Canadian Press.

Transitions can cause ‘the greatest grief’

Another concern with the agreement

the AFN Chiefs rejected was whether First Nations children who live off

reserve would be covered by the deal. Under the current system, the

federal government pays for on-reserve child services, while provincial

governments are responsible for paying for off-reserve child services.

“That’s an Indian Act thing, that

racist Indian Act that's been going on since Confederation, and the

federal government will often weaponize that piece of legislation to try

and limit its financial exposure, which is getting in the way of

children and children's childhoods,” Blackstock said.

“What we would rather see, and what

the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal has already ruled, is that the

definition of a First Nations child is not based on some racist

blood-quantum thing called the Indian Act. Instead, it’s the nation's

recognition of its children on or off reserve.”

Transitional periods can be confusing

and can produce the greatest grief, Charlesworth said. Her office would

not have oversight over children, youth and families who are cared for

by their own nations, for example, unless the nation forms an agreement

to have her involved. However, she said she will be watching over the

transition.

In July, Charlesworth released a report into the violent and disturbing death of an Indigenous boy in care, who was referred to as Colby.

Confusion over roles and

responsibilities during the transition to Indigenous jurisdiction may

have led to staff at B.C.’s Ministry of Children and Family Development

not doing due diligence in placing Colby and his siblings with his

mother’s cousin’s family, the report says.

The fine line between jurisdiction and ‘offloading’

Another “very, very important” concern is adequate funding and resources, Charlesworth said.

“I do believe that people that are

involved in this have the best of intentions, but there is always a risk

of this being just like a devolution of responsibility and liability,

frankly,” Charlesworth said.

“From a perspective of what's

called substantive equality, sometimes more resources are necessary than

what’s currently being allocated to redress the wrongs that have

happened over time and to increase the likelihood of success.”

The AFN Chiefs who rejected the federal agreement agree, as does Blackstock.

“There’s a fine line between

jurisdiction and offloading. And that’s what I'm worried the feds are

doing. They’re not funding these other pieces adequately,” Blackstock

said.

Knutson is also concerned that

adequate resources won’t be made available for nations to take back

jurisdiction and says the rejection of the settlement shows some anxiety

is warranted.

“If you’re in the know, it’s not surprising, because it’s what’s been happening for hundreds of years,” she said.

Blackstock is concerned that dealing with child services in a silo isn’t a way to get to equity.

“I have my own question about whether

or not it’s actually another narrow imposition of this western law by

just saying you can have jurisdiction and child welfare instead of a

reclamation and a reaffirmation of those traditional laws, and then the

resources to be able to address them and implement them, and also clean

up the colonial trauma, and that's going to take multiple generations,”

Blackstock said.

She mentioned the Spirit Bear Plan, a

plan passed by the Assembly of First Nations in 2017, as being a

‘master plan’ that would eliminate inequities on several levels, rather

than with a siloed approach.

The plan calls for specific

changes to address this, including ending the practice of discriminatory

funding and policies, and that public servants receive adequate

training on the TRC’s Calls to Action.

“It said, ‘Let’s break this

pattern of just picking one topic and then throwing a little bit of

money at it, but never getting to equities,” Blackstock said.

“Water is a good example of that.

There’s no excuse for there not being clean water for every First

Nation. I mean, for Pete's sake, they have clean water in the space

station, population six, right? They can do this.”

She said racial discrimination, particularly against children, should never be a fiscal restraint measure.

“You can tighten the belt for

everybody, but you can’t just pick out one group and say, well, you’re

just going to have to be patient and wait,” Blackstock said.

“Sorry, that’s disgusting, but that's what's been going on in Canada. It’s really an apartheid public service system.”

‘Wherever Indigenous children and

youth are,’ Knutson told The Tyee, ‘[I would hope] that they’re able to

be connected to their nation, to their land, to their culture, to their

language.’ Photo courtesy of Jessica Knutson.

‘First Nations are transforming systems’

Regional Chief Terry Teegee spoke about at the Our Children, Our Way conference about his

nephew, who was in foster care, but then was adopted by Teegee’s

mother. He started playing hockey and was successful in school. He’s now

a dermatologist in British Columbia.

In contrast, Teegee spoke about

walking through the Downtown Eastside and thinking about the lost

opportunities for the people living there. Many of them lived through

the child “welfare” system, which Teegee linked with homelessness, the

opioid crisis and the justice system.

“First Nations are transforming

systems that are deeply rooted in racism and discrimination,” he said,

calling this a “pivotal moment.”

Blackstock sees jurisdiction as an

opportunity for First Nations to act more holistically to address the

root causes of children being taken from their families — things like

poverty, addictions or poor housing.

“Those fires are the same things that

disadvantage young people in juvenile justice. It's the same things

that set up young people for mental wellness challenges, the same thing

that sets people up for physical wellness challenges. It's those same

fires, and that's what we have to put out,” Blackstock said.

“To just forget about those

things, let them fester and worsen, and just remove First Nations kids

out of their families, then that's going to lead to another generation

of kids being harmed.”

Having jurisdiction could allow

nations to make decisions to address the community-level trauma that has

been left unattended to for too long, she said.

Across the country, different provinces are working on Indigenous jurisdiction over children. B.C. was the first province to adopt

https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/governments/indigenous-people/new-relationship/united-nations-declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples

the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in

2019.

In 2022, the province became the

first in Canada to recognize the inherent right to self-government for

Indigenous people when it passed Bill 38, The Indigenous Self-Government in Child and Family Services Amendment Act,

which also upholds the right for Indigenous communities to provide

their own child and family services. Since then, several agreements have

been signed between nations and the Ministry of Children and Family Development, a

ministry known mostly for bad news, such as the deaths of children in

care, overworked social workers and being one of B.C.’s most complained

about public entities.

B.C.’s Children’s Ministry has most recently been led by Grace Lore, who was re-appointed after the October 2024 provincial election. She stepped down from her role in early December following a cancer diagnosis.

Before she stepped down, Lore had

promised to overhaul the system, transforming it into one that lifts

families up and focuses on prevention rather than protection.

“We will build a system that is more proactive, that is more flexible, that meets people where they are at,” Lore said.

In September, Lore signed a new accord with the First Nations Leadership Council — the Rising to the Challenge Accord, which

recognizes and upholds that First Nations have the inherent right to

self-determination, including jurisdiction over First Nations children

and families.

“This protocol adds to our evolving

foundation and ongoing joint commitment for how we will work together

with a goal to achieving real and positive change in the coming years,”

said Cheryl Casimer, political executive at the First Nations Summit,

when the report was released.

The bottom-line hope is that children will thrive when cared for by their own nations.

“My Elder talks about how it takes a

child to raise a village. Our future will be better if we attend to the

well-being of the children, because we will be a stronger village if our

children thrive,” said Charlesworth.

For her part as a survivor of the

child “welfare” system as it’s operated in recent decades, Knutson is

hopeful that one day, when more Indigenous nations have reclaimed

jurisdiction, there will be a decrease in the overrepresentation of

Indigenous children in care.

“[I would hope that] wherever

Indigenous children and youth are, that they’re able to be connected to

their nation, to their land, to their culture, to their language, which

has been proven time and time again to be protective factors for

Indigenous children and youth in care, and in the aging out process,”

Knutson said.

As all the voices in this story have

urged, the approach will need to address the root causes that lead to

children being taken from their families — poverty, intergenerational

trauma, addictions, mental and physical health or poor housing.

“There is nothing more important than the health and well-being of our children, our future generations,” said Casimer.

Tracy Sherlockis a freelance journalist and journalism instructor based in Vancouver. She is the editorial lead for the Spotlight: Child Welfare project.

With research by Jeevan Sangha and editorial consultation by Anna McKenzie.

Editor’s note: This story was produced as part of Spotlight: Child Welfare, a collaborative journalism project that aims to improve reporting on the child welfare system. It was originally published by The Tyee. Tell us what you think about the story here.