|

| Canadian Pacific - A surveyor for the Canadian Pacific Railroad must fight fur trappers who oppose the building of the railroad by stirring up Indian rebellion. |

BLOGGER changed, not allowing us to UPDATE this back-up blog

Thursday, November 28, 2024

1949 MOVIE: Canadian Pacific | Randolph Scott

Wednesday, November 27, 2024

Scalp Bounties | DAY OF MOURNING | Thanksgiving in Plymouth

👉 “Bounty” shows daily at the Old State House and can be viewed online

at the Upstander Project’s website, which also features a timeline and a

teacher’s guide to the film and the issues it deals with.

New film at Old State House highlights Cambridge’s ties to colonial ‘scalp bounties’

By Beth Folsom |November 11, 2024

|

| Spencer Phips’ scalp bounty proclamation issued in 1755. (Image: Penobscot Nation Museum) |

“Bounty,” the newly installed film at Boston’s Old State House, is only nine minutes long, but its powerful and disturbing message looms much larger for audiences. Whether tourists or locals, visitors to the Old State House usually expect to tour the 1713 building to glimpse the legislative history of Massachusetts, particularly the events and public debates surrounding the Stamp Act, the Boston Massacre and other aspects of Revolutionary history. Now part of Revolutionary Spaces, which also oversees the Old South Meeting House, the Old State House is sharing the history of brutal attacks on New England’s Indigenous peoples as part of Massachusetts colonial policy – a legacy that is surprising and unnerving to those used to a purely celebratory telling of the colony’s story.

The exhibit, housed in the Old State House’s council chamber, tells the story of so-called “scalp bounties” – one that has a direct connection to Cambridge as a whole and, in particular, to History Cambridge’s headquarters at 159 Brattle St. The adopted son of Sir William Phips, the first governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, Spencer Phips entered politics in his own right in 1721 when elected to the provincial assembly. His family connections had set Phips up for political and economic prominence and, several years after his graduation from Harvard in 1703, he bought a large tract that encompassed much of what is now East Cambridge and settled there with his family.

Phips was appointed to the governor’s council in 1721, and from 1732-1757 was the lieutenant governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, which included the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the Plymouth Colony, the Province of Maine, Martha’s Vineyard, Nantucket, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. During two periods (1749-53 and 1756-57) Phips served as acting governor while William Shirley was abroad.

As a prominent landowner and politician, Phips had set his children up to marry well; in the 1730s Phips’ daughter Rebecca married the up-and-coming merchant and land speculator Joseph Lee and settled into 159 Brattle St., known commonly as the Hooper-Lee-Nichols House. While we do not have direct evidence that this house, which serves as the headquarters of History Cambridge, was occupied by enslaved people on a permanent basis, we know that Joseph Lee and Rebecca Phips enslaved two men, Caesar and Mark Lee/Lewis, on other Massachusetts properties that they owned, and it is likely that one or both stayed with the Lees when they were at their Brattle Street property. Spencer Phips, too, was an enslaver, holding five people in bondage, so his children would have grown up expecting to be waited on by enslaved servants.

In addition to his land in Cambridge, Phips was part-owner of a large tract on what is now the central coast of Maine (then part of the Province of Massachusetts Bay). In 1719, the owners began to develop the land for white settlement to the objection of the local Abenaki People, who argued that their leaders had made land grants to the colonists without authorization from the tribe. Conflicts increased in the 1720s, leading to what is known as Dummer’s War from 1723-1727. For the next several decades, tensions flared between the Abenaki and the colonists, leading Shirley to declare war on the Abenaki in 1754.

In its declaration of war, Massachusetts made an exception for one group of Abenaki: the Penobscot People, whom the colonial government claimed were exempt from their attacks. In reality, the position of the Penobscot made them vulnerable to the same brutality at the hands of colonists as other Abenaki. In the ongoing colonial battles between the English and the French, Indigenous peoples were pressured to take sides; although the Penobscot desired to remain neutral, their geographic location meant that they could not escape colonial politics. Seen as pro-British by the French and pro-French by the Maine colonists, the Penobscot found themselves pushed increasingly toward French alliance because of incidents such as a 1755 attack by New England militiamen on a Penobscot fishing party.

In 1755, while Shirley was away from the colony, Phips issued a declaration of war against the Penobscot, offering cash rewards for each scalp of a Penobscot person turned into the colonial government. Phips’ proclamation put a value of 50 pounds for males over age 12, while women and male children under 12 were deemed to be worth 25 pounds and female children were worth 20 pounds. The next year, the colonial assembly voted to allow scalp bounties of up to 300 pounds – by far the largest sum ever offered in a wartime declaration. In 1759, Massachusetts Gov. Thomas Pownall seized control of the Penobscot River and the homelands of the Penobscot people by force.

Phips signed the declaration of war and the scalp bounty proclamation in the council chamber of the Old State House; in 2021, Upstander Project created a short film featuring several current-day Penobscot families reading the text of the proclamation aloud in the chamber. Penobscot Nation tribal ambassador Maulian Bryant emphasized the importance of not only telling the story of the Phips Proclamation, but doing so in the physical space where these and other decisions were made that so greatly affected the Penobscot and other Indigenous peoples:

It conveys this empowering sense of resilience and that Penobscot people, Indigenous people all over this country were not supposed to still be here. That there were very systematic attempts to exterminate our people in order to have our land taken. So the fact that we are still living here in our home, and we will grapple with this trauma and we will reflect on it and honor our ancestors, but we need to do that by being strong, proud Penobscot people. And this project was a way to reclaim some of that space.

History Cambridge is proud to partner with the Upstander Project to work toward the amplification of Indigenous voices and a broader understanding of local Indigenous histories during this Native American Heritage Month and well beyond.

🦃THANKS BRADFORD?

Plymouth still celebrates (of course)

I do not... Trace

|

The first National Day of Mourning event was held on Thanksgiving Day, November 26, 1970 on Cole's Hill in Plymouth, Massachusetts. James delivered an amended speech[1] beside a statue of Ousamequin, including

| "We forfeited our country. Our lands have fallen into the hands of

the aggressor. We have allowed the white man to keep us on our knees.

What has happened cannot be changed, but today we must work towards a

more humane America, a more Indian America, where men and nature once

again are important; where the Indian values of honor, truth, and

brotherhood prevail.

|

The event was attended by close to 500 Native Americans from throughout the United States[1] and has been held annually on the fourth Thursday in November every year since. James' speech was one of the first public criticisms of the Thanksgiving story from Native American groups.[2]

DAY OF MOURNING: NOVEMBER 28, 2024

HEADLINES

Seattle Magazine: Chef Overcomes Personal Troubles to Celebrate his Native American Roots

Arizona Republic: Thanksgiving always reflected culture. Indigenous chefs are reclaiming it

Sunday, November 24, 2024

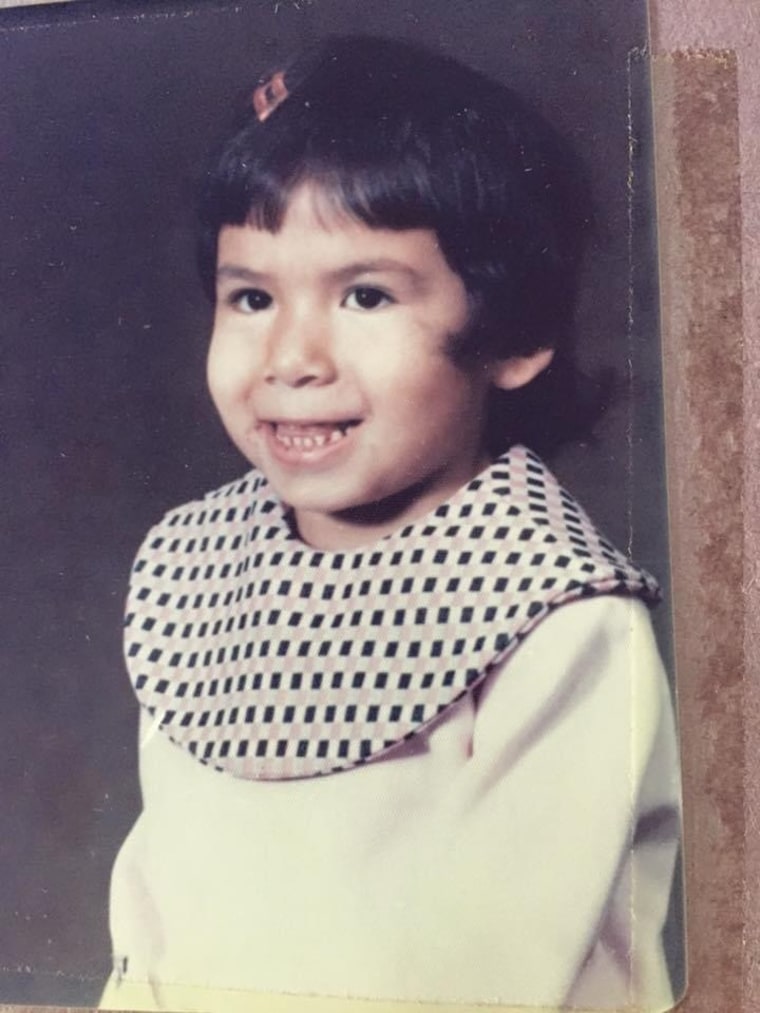

I thought my biological family didn’t want me. But they'd never stopped looking for me

"I felt so much pain that I had been carrying melt away."

When I was a toddler, I was stolen from my home in the middle of the night. Child welfare authorities banged on the door and said, “We’re here for Yvette,” and my parents had no choice but to hand me over.

I’m one of more than 20,000 Indigenous children in Canada who were ripped from their families during what is known as the Sixties Scoop. The Canadian goverment believed that Indigenous people were not fit to raise children. In the words of former prime minister Hector Langevin, “To educate the children properly we must separate them from their families. Some people may say that is hard but if we want to civilize them we must do that."

Similar things happened in the United States, where an estimated 25% to 35% of Native American children were removed from their families before the Indian Child Welfare Act was established in 1978.

My siblings — I’m the youngest of 14 — were sent to federally operated, Catholic boarding schools where they were given English names and forbidden from speaking their aboriginal language. In these programs of forced assimilation, many experienced horrific physical, sexual and emotional abuse.

I was more fortunate.

In 1974, I was adopted by a white Christian couple in Oregon. They were told by the adoption agency that my biological parents didn’t want to raise me. For decades, I believed that story, too.

It was quite easy for a white couple to adopt an Indigenous child at the time. My adoptive parents started the paperwork in January, flew up in March to meet me for the first time, and the very next day they took me back to their home in Oregon.

Growing up, I was aware that I was Indigenous, but it’s not something that I embraced. At school, my classmates called me an Indian. Redskin was another one I heard a lot. My mom says I always asked her to buy me white tights so my legs would look white like the other girls. I didn’t want brown skin. I didn’t want to be different.

It wasn’t until my 20s that I started to get more curious about my history. My brother, who is half Japanese, had started looking for his biological family, so I decided I would, too. I knew my birth parents had the same name, Acoby, so I started by writing to every Acoby I could find in the Canadian providence of Manitoba.

The first person I heard back from was my sister Lorraine, who shared that we are members of Swan Lake First Nation. She said our parents had never stopped looking for me. When I read those words, I felt so much pain that I had been carrying melt away. I had spent my life believing that they didn't want me.

From Lorraine I learned about how our sister Charlotte was taken at a doctor's appointment when she was 5 months old. My mom handed Charlotte over to a nurse, not realizing she would never hold her baby again. My mom went back to that doctor's office every single day for months begging for them to let her see Charlotte, but she was gone.

At the age of 24, I reunited with my mother. My dad, a former chief of Swan Lake, had died a few years earlier. My sisters were there to translate for our mom who spoke only Ojibwe. She was relieved to learn I was raised by kind parents. For all those years she had wondered if I was OK, and I’m glad she was able to have some closure.

It’s so hard to put into words what it was like to be surrounded by people who look like me. There’s this feeling of acceptance. But at the same time, I feel so Caucasian when I’m around my biological family. Sometimes I feel like I don’t belong anywhere, which is not uncommon for survivors of the Sixties Scoop.

Since reconnecting with my birth family, I travel to Swan Lake reserve every summer. I feel at peace there. It’s just prairie land and it’s a part of me that I didn’t know I had been missing.

Now I have sisters that I text and call. We do big family dinners. When we’re together there is this overwhelming sense of calm.

I love sitting around with the council people and learning about where I came from. At my first powwow, I met family members I never knew existed — aunts, uncles, cousins. Unfortunately, the tribe can’t recognize me as a family member because the Canadian government erased my birth certificate. But I do have my Ojibwe name, which means Morning Sky in English. My kids now want to get their spiritual names.

I'm working to get my real birth certificate. The one I have now lists my adoptive parents as my parents.

I received a $25,000 apology check from the Canadian government. And that’s what my life is worth in their eyes. It’s like, "We destroyed your entire family. We took you from your home, from your family. Here’s a check for $25,000.” That hurts a lot.

There are so many people that don’t know anything about what happened to my people during the Sixties Scoop. One summer, I stopped at a burger stand just a few miles from Swan Lake and the woman working behind the counter had never heard of the Scoop.

I want the government to acknowledge what they did and honor those children who never made it out alive from their schools. Let’s call it what it is: The Sixties Scoop, like the Holocaust, was a genocide.

At least 4,120 children are known to have died in the residential schools in Canada. In the U.S., a federal investigation found that at least 973 children died in residential schools — and the actual number is probably much higher, since many were buried in unmarked graves.

My siblings were sent to those schools. They say their hair was cut off. They were beaten for speaking our language and singing our songs. They were forced to study the Bible. My sister Yvonne can only talk about it in little tiny segments because it was so traumatic.

We are healing together.

I will never forget how Swan Lake First Nation chief Jason Daniels welcomed me back.

"You're home," he said. "This will always be your home."

Saturday, November 23, 2024

Two Worlds: What Really Happened?

|

| BUY NOW http://amzn.to/2CjtyRr |

reblog from 2017

(The first edition came out in 2012)

GREENFIELD, MA (2017) Tragic, true, heartbreaking, astonishing... those words have been used

to describe the anthology Two Worlds, the first book to expose in

first-person detail the adoption practices that have been going on for

years under the guise of caring for destitute Indigenous children in North America.

What really happened and where are these Native children now?

The new updated Second

Edition of TWO WORLDS (Vol. 1), with narratives from Native American

and First Nations adoptees, covers the history of Indian child removals

in North America, the adoption projects, their impact on Indian Country,

the 60s Scoop in Canada and how it impacts the adoptee and their

families.

"This book changed history," say editor Trace Hentz. "There is no doubt in my mind the adoption projects were buried and hidden... we adoptees are the living proof."

The Lost Children Book Series includes: Two Worlds, Called Home: The Roadmap, Stolen Generations, In The Veins: Poetry and ALMOST DEAD INDIANS (2024). The book series is an important contribution to American Indian history.

Trace Hentz (formerly DeMeyer) located other Native adult survivors of adoption and asked them to write a narrative for the first anthology. These adoptees share their unique experience of living in Two Worlds, surviving assimilation via adoption, opening sealed adoption records, and in most cases, a reunion with their tribal relatives. Indigenous identity and historical trauma takes on a whole new meaning in this adoption book series.

As Hentz writes in the Preface, "The only way we change history is to write it ourselves." This book is a must read for all that want the truth, since very little is known or published on this history."I was asked to update this book by one adoptee contributor and I added a new narrative by Levi Eagle Feather, and more information on the 60s Scoop. Please tell your friends and other adoptees," Trace Hentz says. "One day in America, we Lost Children will have our day in court."

(Since 2012, this anthology has traveled the world, and I hope it helped you!)

On BOOKSHOP: https://bookshop.org/p/books/two-worlds-lost-children-of-the-indian-adoption-projects-vol-1-second-edition-trace-l-hentz/11587960?ean=9780692372104

On Amazon, Kindle, Kobo...

The Ground We Walk On | Wisconsin once home to tens of thousands of burial mounds

By Frank Vaisvilas

Marquette University history professor Bryan Rindfleish put it best when he said there’s a sacredness to the ground we walk on in Wisconsin when you realize that everywhere you step holds thousands of years of Native American history underneath.

He said Increase Lapham, the prominent civil engineer who helped transform Milwaukee from a small village into a booming city, realized that, as well. In the mid-1800s, as developers flattened hundreds of ancient Indigenous mounds all over the city, Lapham saved at least two mounds with his design of Forest Home Cemetery, researchers recently learned.

But, as Rindfleish points out, that didn’t stop Lapham or the cemetery owners at the time from burying people along the edges of the mounds.

About 20,000 mounds, effigy and conical, were built in Wisconsin. Only about 4,000 remain today, partly because of development over the last 200 years. They also were destroyed by amateur archeologists and ordinary Wisconsin residents.

It was not uncommon for Wisconsin families to have Sunday picnics on top of these mounds and then spend the rest of the afternoon digging for artifacts and even human remains to keep in their private collections, or to sell to museums or universities.

Early non-Native settlers in Wisconsin had theorized in the 1800s that the mounds were built by some “lost race” or even the Vikings because they couldn’t accept that Native Americans, whom they were removing from their lands at the time, would be capable of creating such massive and impressive earthworks.

Later researchers determined that the effigy mound systems closely resemble the clan systems and spirit animals still used by many local Indigenous tribes today, such as the Thunderbird and Water Panther.

Conical burial mounds started being built in Wisconsin around 500 B.C. Effigy mounds depicting people, animals or spirits were built from about 700 A.D. to around 1100.

There is still some debate about which tribe, exactly, built the mounds, especially those in southeast Wisconsin.

The Ho-Chunk Nation has taken the lead today in protecting remaining mounds from development, and its historians and elders claim their ancestors built the mounds, especially in central and southwestern Wisconsin.

The Potawatomi claim southeast Wisconsin as their ancestral homeland, but Menominee tribal historians claim their tribe’s ancestral territory included all of what is now known as Wisconsin, as well as parts of Illinois, Michigan and Minnesota. Menominee historians say the Menominee were here before any other tribe and any other people dating back at least 10,000 years.

This debate between tribal historians tends to heat up when there’s any push or movement for a new casino in Kenosha and whether it will be owned and operated by the Menominee Nation, currently among the most impoverished of tribes.

If you like this newsletter, please invite a friend to subscribe to it. And if you have tips or suggestions for this newsletter, please email me at

fvaisvilas@gannett.com.

|

https://www.greenbaypressgazette.com/story/news/local/wisconsin/2024/11/14/ancient-indigenous-mounds-found-at-milwaukees-forest-home-cemetery/76221371007/

Friday, November 22, 2024

New law is unlocking secrets of closed Minnesota adoptions

More than 2,800 Minnesota adoptees have already requested copies of their original birth records. Very few are finding contact preferences from their birth parents.

MINNETONKA, Minn. — From the moment a law change gave Minnesota adoptees the right to access their original birth records, Lisa Belknap knew she'd be applying the first chance she got.

She just never imagined it would arrive in her mailbox on her birthday.

"I'm shaking," said Belknap, who invited KARE11 to be there as she opened her birth record. "I thought... just how remarkable that is, to get your birth certificate on your birthday, for the first time. The real one."

Like many Minnesotans who were involved in closed adoptions, Belknap spent most of her life with very little information about her birth parents. Limited information about their medical history, along with a few baby photos from her six weeks in foster care, were her only clues to her past.

But while she always wondered where she came from, she wants to make it clear that she never wondered who her family is. She was quickly adopted by loving parents, and an older brother.

"Do they feel uncomfortable about the fact that I might find my birth family? Absolutely not. No," Belknap said. "I think the main thing my parents have always been concerned about is what I might find."

Birth Parent Contact Preference

Because any Minnesota adoptee who is 18 or older can now request their birth record and attempt to find their birth parents, the state spent a year trying to publicize the changes and give birth parents a chance to offer their contact preferences.

"We asked them to fill out a Birth Parent Contact Preference form," said State Registrar, Molly Mulcahy Crawford. "There's a space where they can share anything they want. Maybe their address, maybe how to get ahold of me if they want contact, maybe to explain why I don't want contact."

Despite those efforts, and a potential pool of 175,000 Minnesota adoptions, fewer than .5% of birth parents have returned that form in the last year.

Mulcahy Crawford: "In total, we've received 377 birth parent contact preference forms."

Erdahl: "Do you know how many said? Yes, I can be contacted versus I prefer not to?"

Mulcahy Crawford: "It's about 50/50, but regardless of that preference, if an adopted person makes a request under the new law, they're going to get a copy."

Erdahl: "In other words, noboby can stop them from still contacting them."

Mulcahy Crawford: "Right."

Despite the minuscule odds of encountering one of those forms, Belknap found one tucked behind her birth certificate.

"She marked that she prefer not to be contacted at this time," she said, with tears in her eyes. "And she wrote, 'Just please respect my request of no contact.'"

As a mother herself, it's a request she can't fathom.

"One of the probably most profound moments of my life was when my daughter was born and I just remember looking at her and that was the first person in my entire life that I had a biological connection with," Belknap said. "It's disappointing to know that there's that much forethought into not wanting to know me."

Searching for Clues

Knowing her birth mother's preference didn't stop Belknap from trying to find her online.

"It's not her choice anymore," she said. "She made her choice for me when I was a baby and I didn't have a say in that. As an adult now it's, it's my decision on how I wanna handle this."

Within just a few minutes of searching Facebook, Belknap and her husband were very confident that they had found her birth mother.

"She seems to be a really proud grandma," Balknap said, looking through several photos publicly available on Facebook. "I can relate because my mom is really proud of my kids too."

That realization is a major reason why her search stopped there.

"I don't think I would be true to myself if I disrespected her wishes," Belknap said. "As much as I want to, my parents didn't raise me to be that way."

Still a Gift

Despite her disappointment in her birth mother's reply, Belknap says she's still grateful for her records.

"Any information to connect me to my past is a gift," she said. "What I would want birth parents to know is - at least for me as an adoptee and other adoptees that I've spoken to - is we're not trying to get something from someone. I think most people just want to know their origin story."

For more information on the state law change, and how to request birth records, click here.

My family experienced Indian boarding schools – and genocide

This article was originally published by The Conversation and is republished here by permission. Read the original article.

I am a direct descendant of family members that were forced as children to attend either a U.S. government-operated or church-run Indian boarding school. They include my mother, all four of my grandparents and the majority of my great-grandparents.

On Oct. 25, 2024, Joe Biden, the first U.S. president to formally apologize for the policy of sending Native American children to Indian boarding schools, called it one of the most “horrific chapters” in U.S. history and “a mark of shame.” But he did not call it a genocide.

Yet, over the past 10 years, many historians and Indigenous scholars have said that what happened at the Indian boarding schools “meets the definition of genocide.”

From the 19th to 20th century, children were physically removed from their homes and separated from their families and communities, often without the consent of their parents. The purpose of these schools was to strip Native American children of their Indigenous names, languages, religions and cultural practices.

The U.S. government operated the boarding schools directly or paid Christian churches to run them. Historians and scholars have written about the history of Indian boarding schools for decades. But, as Biden noted, “most Americans don’t know about this history.”

As an Indigenous scholar who studies Indigenous history and the descendant of Indian boarding school survivors, I know about the “horrific” history of Indian boarding schools from both survivors and scholars who contend they were places of genocide.

Was it genocide?

The United Nations defines “genocide” as the “intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.” Scholars have researched different cases of genocide of Indigenous peoples in the United States.

Historian Jeffery Ostler, in his 2019 book “Surviving Genocide,” argues that the unlawful annexation of Indigenous lands, the deportation of Indigenous peoples and the numerous deaths of children and adults that occurred as they walked hundreds of miles from their homelands in the 19th century constitute genocide.

The mass killings of Indigenous peoples after gold was found in the 19th century in what is now California also constitutes genocide, writes historian Benjamin Madley in his 2017 book “An American Genocide.” At the time, a large migration of new settlers to California to mine gold brought with it the killing and displacement of Indigenous peoples.

Other scholars have focused on the forced assimilation of children at Indian boarding schools. Sociologist Andrew Woolford argues that scholars need to start calling what happened at Indian boarding schools in the 19th and 20th century “genocide” because of the “sheer destructiveness of these institutions.”

Woolford, a former president of the International Association of Genocide Scholars, explains in his 2015 book “This Benevolent Experiment” that the goal of Indian boarding schools was the “forcible transformation of multiple Indigenous peoples so that they would no longer exist as an obstacle (real or perceived) to settler colonial domination on the continent.”

Indigenous writers have explained how this transformation at Indian boarding schools occurred. “Federal agents beat Native children in such schools for speaking Native languages, held them in unsanitary conditions, and forced them into manual and dangerous forms of labor,” writes Indigenous law professor Maggie Blackhawk.

What my grandmother witnessed

Secretary of the Interior Debra Anne Haaland has stated that every Native American family has been impacted by the “trauma and terror” of Indian boarding schools. And my family is no different.

One of the more horrific stories that my maternal grandmother shared with her grandchildren was that she witnessed the death of another student. They were both under the age of 10. The student died of poisoning after lye soap was put in her mouth as a punishment for speaking her Indigenous language.

Read High Country News’ past coverage about Indian boarding schools:

- Washington works to reconcile its history of Indigenous boarding schools

- Native mental health providers seek to heal boarding school scars with informed and appropriate treatment

- Who does the federal boarding schools investigation leave out?

- The true stakes of the Indian Child Welfare Act

- The night the Greyhounds came

- The children at rest in 4-H Park

- Indigenous college faculty and students lead the removal of racist panels in Colorado

- Interior looks into the legacy of Native boarding schools

- The U.S. stole generations of Indigenous children to open the West

- Where are the Indigenous children who never came home?

We know that similar punishments happened and children died at Indian boarding schools. The Department of Interior reported in 2024 that 973 children died at Indian boarding schools.

Tribes are increasingly seeking the return of the remains of children who died and are buried at Indian boarding schools.

Lasting legacy

The U.S. government is beginning to encourage survivors to tell their stories of their Indian boarding school experiences. The Department of the Interior is in the process of recording and documenting their stories on digital video, and they will be placed in a government repository.

At 84 years old, my mother is the only living Indian boarding school survivor in our family. She shared her story with the Department of the Interior this past summer, as did dozens of other survivors.

Haaland stated these “first person narratives” can be used in the future to learn about the history of Indian boarding schools, and to “ensure that no one will ever forget.”

“For too long, this nation sought to silence the voices of generations of Native children,” Biden added at the apology ceremony, “but now your voices are being heard.”

As a descendant of Indian boarding school survivors, I appreciate President Biden’s apology and his effort to break the silence. But, I am also convinced that what my mother, grandmother and other survivors experienced was genocide.

SOURCE: https://www.hcn.org/articles/my-family-experienced-indian-boarding-schools-and-genocide/

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons license.

Wednesday, November 20, 2024

Adoption Reality: Forced Adoption Scotland

After 50 years of silence, victims of Scotland’s forced adoption scandal demand redress

The Scottish Government must compensate the victims of the forced adoption scandal, now that it has accepted responsibility, a leading lawyer has said.

Experts say the injustice of taking babies from their mothers simply because they were not married compares with the harm caused by both the infected blood and in-care abuse scandals.

Solicitor Advocate Patrick McGuire, who heads negligence firm Thompsons Solicitors, told a round table inquiry in the Scottish parliament last week: “When Former First Minister Nicola Sturgeon delivered the forced adoption apology last year on behalf of the state, she accepted responsibility for what happened.

“Accepting that responsibility comes with the unanswerable requirement to create a redress scheme to help victims recover from the trauma and harm they suffered.”

Forced adoption scandal

Calling on victims to ditch the guilt cruelly imposed upon them for over 50 years, McGuire said: “The forced adoption scandal saw vulnerable women shamed into silence for decades, an unjust shame which remains a factor today over why so many still have not felt able to come forward to seek justice.”

McGuire, whose expert team has been investigating the injustice and human rights abuses inflicted upon Forced Adoption victims until the practice was halted in the late ’70s, said all those involved suffered lifelong harm.

Bullied, threatened with jail if they tried to find their children, and lied to over their legal rights, he warned the psychological damage inflicted upon 60,000 mothers, their children and families is still causing trauma today.

© Andrew Cawley

© Andrew CawleyOn behalf of the Scottish Government, former First Minister Nicola Sturgeon delivered an unreserved apology in March 2023. She said: “Ultimately, it is the state which is morally responsible for setting standards and protecting people. As modern representatives of the state, I believe we – among others – have a special responsibility to the people affected. We have a responsibility to do whatever we can to support them, in dealing with the legacy of what happened.”

She added: “The issuing of a formal apology is an action governments reserve for the worst injustices in our history. Without doubt, the adoption practices which prevailed in this country for decades fit that description.”

McGuire said: “Forced adoption shares hallmarks with the infected blood scandal and the thousands of children in care who suffered appalling sexual and physical abuse decades ago in residential school and homes.

“Individuals were treated inhumanely decades ago, in circumstances that were ultimately the responsibility of government.

“The government recognised their responsibility in the formal apologies which followed, just as they did for forced adoption.

“Forced adoption victims have been shamed into silence for decades, and that unjust shame remains a factor today over why so many victims still have not felt able to come forward to seek justice.”

‘No excuse’

McGuire, who has championed victims harmed by exposure to deadly asbestos, mesh-injured patients and bereaved families in the hospital inquiry, told MSPs there is “no excuse” for the Scottish Government to delay delivering redress to forced adoption victims.

He said: “As they did in both the infected blood and in-care abuse scandals, Westminster and Holyrood decided, purely on the basis of a moral case, to create compensation schemes after recognising their responsibility for what happened. The Scottish Government already have the blueprint for redress schemes. They must proceed without delay.

“Without The Sunday Post exposing this dark, hidden episode in Scotland’s history, the victims of forced adoption would have continued suffering some of the worst examples of injustice I’ve ever encountered.

“It’s deeply upsetting so many mothers who had their babies taken from them have passed away without getting justice.

“That is why it is incumbent upon the government to do the right thing as a matter or urgency. The scandal becomes ever more shameful as time passes and more victims are denied justice for something which never should have happened.”

The campaign

Supported by MSPs Monica Lennon and Miles Briggs, campaign group Forced Adoption Scotland, who secured the apology, is calling on victims to put aside the shame unjustly forced upon them to come forward and seek redress.

© Andrew Cawley

© Andrew CawleyCampaigner Marion McMillan, 74, said: “We’ve been silenced for over 50 years. Our legal and human rights were taken from us at the same time our babies were torn from our arms and given to married couples as we wept.

“Times have changed so radically; we recognise how difficult it must be for people today to fully understand what was done to us. We were terrified of authority, threatened with being thrown in jail if we tried to find our babies. We were told we were worthless, not fit to be mothers simply because we fell in love outside of marriage.

“Nobody at Forced Adoption Scotland made a lifestyle choice to give their baby up. If what was done to us was attempted today, those responsible would be behind bars. The Scottish Government did the right thing by delivering a formal apology. But since then, they’ve failed to engage with Forced Adoption Scotland and failed to keep the promises they made to our mothers, adoptees and families who have suffered unbearably.

“Because of those failures, we believe the only way forward now is for a redress scheme. We need funds to pay for the specialist support and counselling to repair the damage done to us.”

Forced Adoption Scotland adoptee Marjorie White, 73, said: “After recognising the harm done to us, the Scottish Government then tried to do things on the cheap by funding counselling services from inexperienced groups with no experience of dealing with the kind of the trauma we suffered.

“At the same time, experienced trusted organisations like Birthlink have not been given adequate government funding to provide the support and services we need, and they are best at delivering.

“When Nicola Sturgeon delivered the formal apology, we were full of hope that after decades of silence and pain, at last our suffering would end and the wrongs of the past would finally be recognised.

“She promised all victims would get the help and support we needed to recover from the harm we suffered, the trauma of having our identities taken from us and the years of searching and never getting answers because the adoption system prevented us.

“But after she stepped down as First Minister, those who were supposed to keep the promises she made failed us dismally. In fact, the blundering attempts they made to provide support which was entirely unsuitable have caused even further damage. That is unforgivable.

“Government ministers and officials have made little or no attempt to work alongside Forced Adoption Scotland despite our decades long fight for the formal apology and our success achieving it.

“Our group contains members from every side of the adoption scandal, but there has been no consultation with us. Adoptees in particular have been left out of discussions. We all matter. We all suffered lifelong harm and distress.

“I have spent much of my adult life receiving counselling for what was done to me, and I have trained as a counsellor so in effect I could try and heal myself. When I compare the quality of the services the government are offering, I have more experience than those being paid public money to supposedly help us. It’s unacceptable.”

The Scottish Government said: “Our deepest sympathies are with the mothers, adoptees and families who have endured immense pain and suffering as a result of these unjust practices.

“We recently held sessions with mothers and adoptees. We are taking forward actions based on these discussions, and we continue to fund the charity Health in Mind to offer specialist support to those affected by historic adoption.”

If you’re a victim, you can contact Forced Adoption Scotland on Facebook and Thompsons Solicitors Scotland on 0800 0891 331 or on WhatsApp. The Sunday Post’s chief reporter is Marion Scott – mascott@sundaypost.com

click

Contact Trace

NO MORE UPDATES

GO TO: https://blog.americanindianadoptees.com/ for updates and news. THIS BLOG cannot be updated...

-

Published on Sep 28, 2013 This 40-minute documentary explains the reason for and the process of creating and implementing ...

-

Editor NOTE: This is one of our most popular posts so we are reblogging it. If you do know where Michael Schwartz is, please leave a com...

-

By Melanie Payne ( mpayne@news-press.com ) August 15, 2010 Alexis Stevens liked to describe herself as a model citizen. She was adopted fr...

-

By Mary Charles I somehow don't believe the intention was for us (adoptees) to find our homes using DNA. But when I came across t...

-

By Trace L Hentz, blog editor I have often wondered about how we adoptees were affected by our adoptions, as far as our mental health. (I ...

-

By: Shannon Logan Feb 07, 2014 Leland Morrill was estranged from h...

-

South Carolina court drops contempt charge against Dusten Brown Dusten Brown and the Cherokee Nation rea...

-

By Trace L Hentz (formerly DeMeyer) Watching clips of today’s episode (10-18-12) of Dr. Phil, watching those teary adoptive parents s...

-

Capobiancos Sue Dusten Brown for Nearly Half a Million in Fees Suzette Brewer September 25, 2013 As Matt and Melanie...

-

Anger turned inside: The Fight For Native Families By Trace Hentz (formerly DeMeyer) I am 57 years on the long road as an adoptee w...