DULUTH, Minnesota — Should Native American blood continue to be a tribal citizenship requirement?

That's

the question facing the 34,000 adult citizens of the Minnesota Chippewa

Tribe (MCT) who are being asked whether to amend a critical piece of

the tribe's controversial Constitution. It's a document that dictates

its citizenship, rights, elections and governing body that was forced

upon them by the federal government more than 60 years ago.

The

vote is decades in the making as tribal leaders studied the issue.

Ballots are set to be mailed for what's known as a blood quantum vote on

June 14. (see update below)

Since 1961, membership in the six-nation tribe

requires a minimum of 25% Minnesota Chippewa Indian blood, or blood

quantum, stemming back to 1941 membership rolls kept by the federal

government. The requirement has had the effect of shrinking the tribe's

enrollment, with many children not considered members despite parents

who are.

"We

need to do something soon, as the end of the line is very near," said

Wayne Dupuis, a member of the Fond du Lac band who has worked on

Constitution reform for more than 40 years. Dupuis' three children were

denied Fond du Lac citizenship nearly two decades ago because of the

blood quantum rule. Dupuis said membership to the tribe should reflect

its values and customs, not a calculation "determined by a law of

diminishing returns.

Not

everyone agrees. Some worry already limited federal funds will have to

be spread thinner or that more people taking advantage of treaty rights

for wild ricing or hunting will make resources scarce.

When

the blood rule was adopted in 1961, the Bureau of Indian Affairs

equated Native Americans with "horses and dogs," said Melanie Benjamin,

chief executive and chair of the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe.

"We

as tribal leaders have to make sure we correct all of these terrible

policies that were intended to wipe us out as American Indian people,"

Benjamin said.

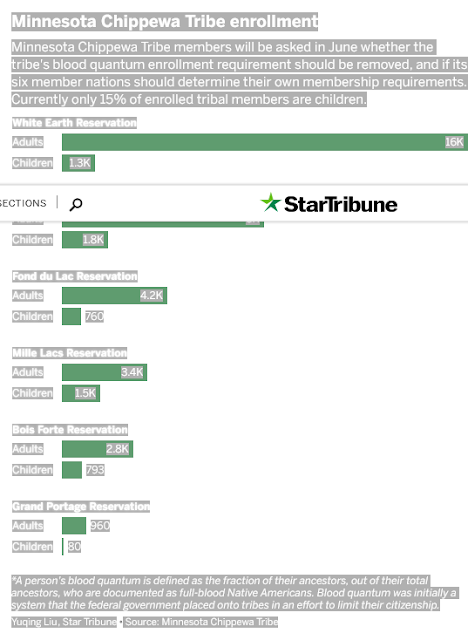

Today,

just 15% of MCT membership — about 40,000 people — is under age 18, a

low figure directly related to the blood quantum rule.

Talk of removing the blood

quantum criteria, as the Cherokee, Seminole and many other tribes have

done, has swirled for decades. In recent years Minnesota Chippewa Tribe

leaders, comprised of those from its six reservations, convened a group

of delegates to study constitutional reform. The group recommended an

initial vote meant to guide tribal leaders in the reform members want

related to blood quantum, its biggest issue. A binding vote could

follow.

Another question is on the ballot: Should the six reservations be allowed to determine their own citizenship requirements?

For

some, the questions are complicated and wrapped in a history of the

federal government's quest to shrink the number of Native Americans

while eradicating their cultures, issues of identity and inclusion, and

practical matters like services and funding.

The

vote signifies reclaiming control of what was "imposed on tribes by the

federal government," said Karen Diver, former chair of the Fond du Lac

Band of Lake Superior Chippewa who also worked for the Obama

administration on Native American issues.

"The ultimate exercise in tribal sovereignty is how you determine citizenship," she said.

Members of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe have voted in a historic

advisory referendum to eliminate a requirement that enrolled members

must have 25% tribal blood.

Out of nearly 7,800 ballots cast, 64% of voters said the “blood

quantum” requirement should be removed from the tribe’s constitution,

which was adopted under pressure from the federal Bureau of Indian

Affairs in the early 1960s.

In a second referendum question, 57% said individual bands or

reservations should be able to determine their own membership

requirements. The Minnesota Chippewa Tribe is made up of six Ojibwe or

Chippewa bands in northern Minnesota, the Bois Forte, Fond du Lac, Grand

Portage, Leech Lake, Mille Lacs and White Earth reservations. Red Lake

Nation is not part of the MCT. More👇

Lasting effects

In the early part of the century, the legal ability of Ojibwe people to sell land was tied to blood quantum.

"Anthropologists

performed physical examinations, including measuring heads and

analyzing hair samples," said Jill Doerfler, a University of Minnesota

Duluth American Indian studies professor and author of a book on blood

quantum. Doerfler grew up on the White Earth reservation and her mother

is a citizen, but Doerfler herself doesn't meet the blood requirement.

Those

deemed by anthropologists to be Anishinaabe, or Chippewa, were listed

on "blood rolls" that were accepted in U.S. courts, Doerfler said.

In

the 1940s and 1950s, the Bureau of Indian Affairs pressured the MCT to

adopt a blood quantum requirement for tribal enrollment. It was done

with the hope that, over time, fewer people would meet the criteria and

Native American nations would eventually disappear, relieving the U.S.

of treaty obligations, Doerfler said.

Tribal

leadership resisted a blood quantum, but eventually adopted it because

of threats to terminate the tribe. Those on a membership roll from 1941

remained citizens, along with their children born before the 1961

change. Those born after needed to meet the 25% requirement. As a

result, in a single family, some children were citizens and some were

not.

"Blood

quantum isn't a real thing and really can't be measured," Doerfler

said. "When people say the rolls are inaccurate, they are referring back

to the physical methodology of determining blood quantum."

About a decade ago the MCT asked

St. Paul-based Wilder Research to study population projections using

different scenarios. It concluded that under current enrollment

criteria, each member nation and the tribe as a whole would experience

"steep population declines" throughout the century, and a "substantial"

number would be over age 65 toward the end.

Using

lineal or direct descent criteria to enroll members, used before the

1961, enrollment among the six reservations would rise between 120,000

to 200,000 by the end of the century, the study says.

People

think blood quantum identifies them, said Sally Fineday, a member of

the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe. "But once you are Ojibwe, you are always

Ojibwe."

'Recognizing our children'

Tribal citizenship is tied to treaty rights,

including those for hunting, fishing and gathering, and some bands

offer payments to members based on casino revenues. Some worry about how

more citizens would affect resource availability or their portion of

casino proceeds. Federal funding for certain types of health care or

housing, for example, may also be spread thinner. Grant funding,

however, which tribes increasingly rely on, could grow with more

citizens.

It's

a "contentious" issue on the White Earth reservation, which has the

largest membership of the six, said White Earth citizen Patty Straub.

"It's difficult enough to receive some of these services," she said, and some are worried that would worsen.

Still others see it as righting a wrong.

"We're

recognizing our children — because what parent doesn't recognize their

child as their child?" asked Cheryl Edwards, a Fond du Lac citizen

working on reform.

The

two things — access to resources and recognizing kin — shouldn't be tied

together, Diver said, but that's how the government arranged it.

"Fundamentally,

this ends up being about identity; the right to claim your identity and

your community and your kinship," she said. "But it doesn't mean it

won't have practical day-to-day impacts and I think that's what people

are struggling with. If you take one away from the other it ends up

being an easier question, but there is no way to do that."

A time for change

Results

of the vote will give tribal leaders direction, but it won't

necessarily dictate removal of the blood quantum requirement. Change

could mean broadening the base of inclusion to all Chippewa, or lowering

the quantum further.

But

something needs to be done, said Cathy Chavers, chair of the Bois Forte

Band of Chippewa and president of the MCT Tribal Executive Committee.

Because

of differing opinions among the six reservations, it's taken decades to

get to this point, she said, and this vote — even in its advisory role —

is "monumental."

A

potential citizenship amendment is only the beginning. Proposals for an

amended Constitution will represent who the Chippewa are, their culture,

vision and origin story.

"It won't look anything like it looks today," Edwards said of the Constitution, "never written by us or for us."