WARNING: This story contains distressing details.

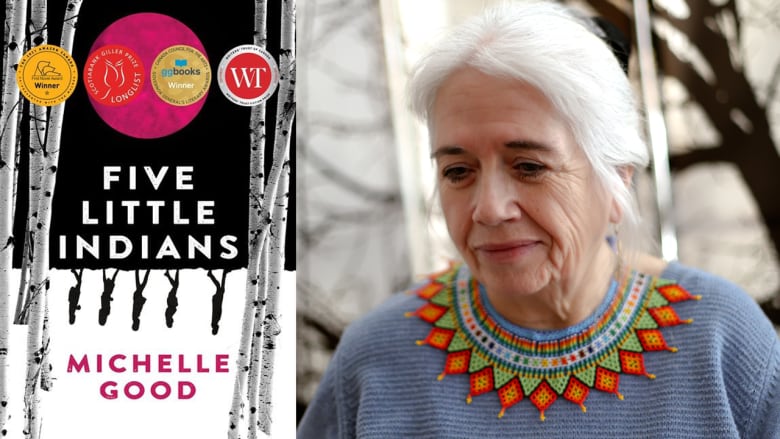

Michelle Good is a writer, retired lawyer and a member of Red Pheasant Cree Nation in Saskatchewan. Her poems, short stories and essays have been published in magazines and anthologies across Canada.

Good's debut novel Five Little Indians is a bestselling book that chronicles the quest of five residential school survivors — Kenny, Lucy, Clara, Howie and Maisie — to come to terms with their past and find a way forward. Released after years of detention, the five teens find their way to the seedy and foreign world of Downtown Eastside Vancouver, where they cling together, striving to find a place of safety and belonging in a world that doesn't want them.

Five Little Indians won the 2021 Amazon Canada First Novel Award and the 2020 Governor General's Literary Award for fiction. The novel has also been optioned by Prospero Pictures to be adapted to screen as a limited TV series.

Five Little Indians will be championed by the journalist and author Christian Allaire on Canada Reads 2022.

Canada Reads will take place March 28-31. The debates will be hosted by Ali Hassan and will be broadcast on CBC Radio One, CBC TV, CBC Gem and on CBC Books.

In May 2021, the Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation in B.C., uncovered the remains of 215 children on the grounds of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School.

The news has had an emotional effect on Good, who is currently based in southern British Columbia. She spoke with Shelagh Rogers about why she wrote Five Little Indians — and why the legacy of Canada's residential school system stays with her.

Calls to action

"That first weekend after the Kamloops announcement was really rough. I told a friend of mine that I felt catatonic after that announcement. It's not because we didn't know. We did know. People have been talking about this for years and years. But there's never been any support to resolve this, to do what the band has done themselves.

"But the thing that really, really bothers me — and it actually infuriates me and I try to stay away from being infuriated — is in 2015, when the Truth and Reconciliation report was issued, there are six calls to action, 71 through 76, that are up here under the heading of 'missing children and burial information.'

"Murray Sinclair and the other commissioners basically gave the federal government a roadmap for how to address this issue through those calls to action. They developed a budget to go with it. And the federal government said no.

I would bet you my bottom dollar, you're going to find one of these grave sites virtually at every residential school.