In Carson City, Nevada more than 170 marked graves have been found at an old Indian school cemetery.

Illnesses, accidents and epidemics took their toll on native students

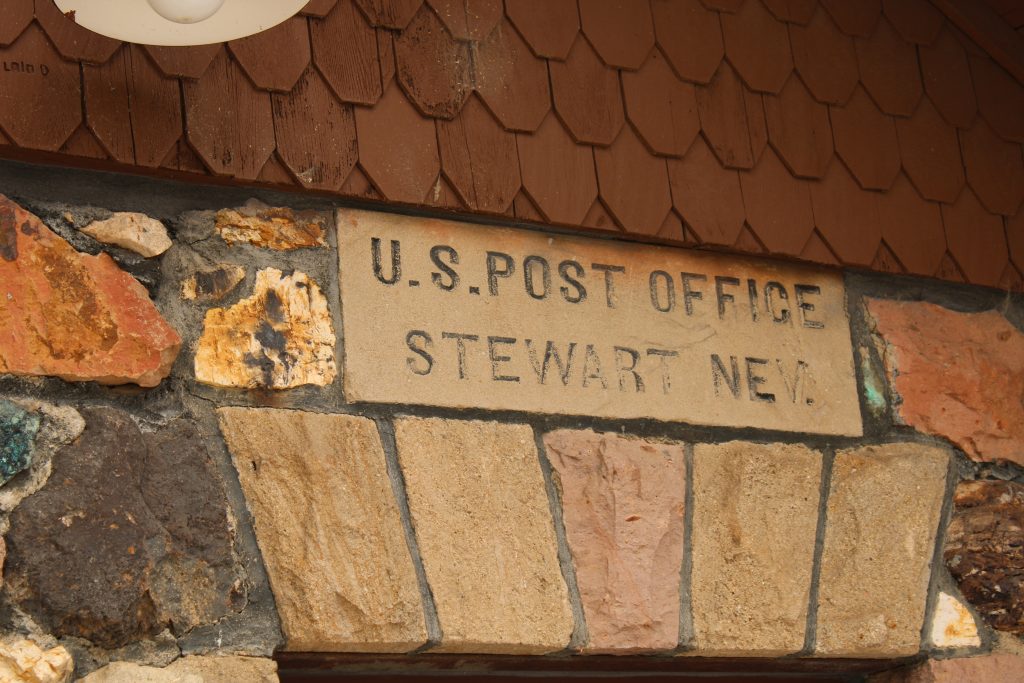

|

| PHOTO/FRANK

X. MULLEN: The cemetery now known as the “Old Stewart Indian Cemetery”

or the “Dat-So-La-Lee Cemetery,” after the master Washoe basket weaver

who is buried there. Most of the stones are simple marble tablets but

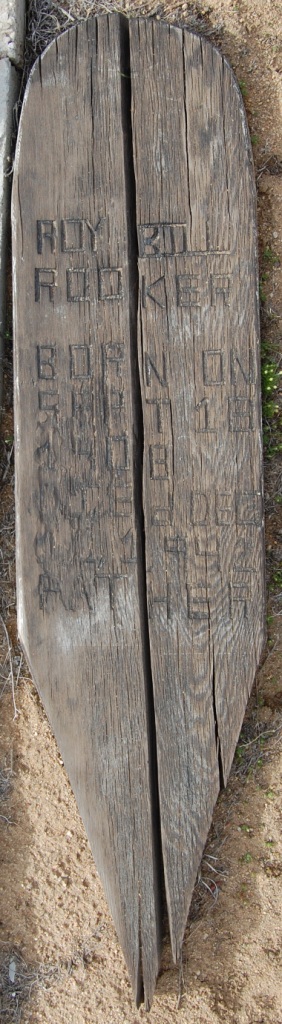

there are also a few wooden, concrete and sandstone markers, as well as

numerous unmarked graves. In the 1940s, a new cemetery was established

less than a mile to the west of the old cemetery. Both are on Washoe

tribal property. Photos used in this story were taken from outside the

fence line. |

Starting in the late 1800s, a system of more than 350 Indian boarding schools was tasked with stripping indigenous Americans of their language and culture, while isolating them from their families and tribes, in an effort to “assimilate” the students into white society.

At Stewart Indian School, which opened in 1890, the very existence and memory of about 200 native people, presumably children, were erased as well.

At the old school cemetery adjacent to the 240-acre campus, southwest of central Carson City, there are more than 170 marked graves. Those range in time from 1880, a year before the school existed, to the early 2000s. The marked gravesites include many with weathered, nearly-illegible headstones as well as easily-read marble markers and well-tended family plots. The wind-swept site on tribal land, protected by a fence and ringed with gnarled sagebrush, also encompasses an estimated 200 unmarked plots, whose occupants and dates of interment are a mystery.

The institution is among hundreds of Indian boarding schools that will be examined by the federal government in an effort to document their histories, including identifying the students who attended them and those who never went home. That review, announced in June by U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, came after nearly 1,000 unmarked graves were found at former Indian boarding schools in Canada.

Stacey Montooth, the executive director of the Nevada Indian Commission, last month inspected the Stewart cemetery and reported her findings to the Interior Department, which decided to add the institution to its review.

“I hope we find the names of every student who attended the Stewart Indian School and find those dates (of attendance) and their tribal affiliations. I’m hopeful that we can share that information with their families, their descendants. Then that will give new insights for their loved ones and allow them to have a new appreciation for the experience of their ancestors or their elders.”

– Stacey Montooth, executive director of the Nevada Indian Commission.

Inherited trauma

Montooth said the review is about more than cataloging names and gathering data. Learning about students’ experiences at the school, she said, could help tribal people understand “some of the dynamics in their families, and with reflection, quite possibly make those families stronger and more grounded in their culture, which would lead to stronger communities.”

The history of the Stewart Indian School, the topic of a sidebar to this story, is a mixture of proud achievement and shameful treatment; school spirit, loneliness and resilience. What was called “assimilation” from the early 1800s to the 1930s is today seen as an attempt at cultural genocide, even ethnic cleansing. The boarding schools’ initial goal to “kill the Indian, save the man” failed, but the human price of those policies reverberates down through generations of tribal people.

The costs yet to be tallied include information about those who rest in the unmarked burials among the headstones in the old school cemetery, located on land returned to the Washoe Tribe of California and Nevada. Permission from the tribe is required for entry.

“We must shed light on what happened at federal boarding schools. As we move forward in this work, we will engage in tribal consultation on how best to use this information, protect burial sites, and respect families and communities.”

— Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland.

Some records lost

Montooth said the Nevada Indian Commission is gathering what records are available, but has not yet received specific direction from the Department of Interior about how to proceed. The commission will work with tribal leaders and school alumni during the course of the review, she said.

There is no complete roster of Stewart students, but according to an estimate by the Nevada State Museum, about 30,000 children were enrolled there during the 90-year life of the school. Some pupils attended for many years; others for just a few months. When the institution closed in 1980, some school documents and records were lost and others were sent to federal repositories, said Bobbi Rahder, director of the Stewart Indian School Museum and Cultural Center.

Montooth said that when federal authorities suddenly closed the school, “there was absolutely no transition plan. It was a shock to staff, students, faculty and the state of Nevada.” In addition to the documents stored at federal facilities, she said, some documents and artifacts formerly displayed in the school are now under the control of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and kept in a warehouse in Carson City.

“We’re hopeful that eventually those items will be returned to the Nevada Indian Commission, especially in light of the Secretary of the Interior’s initiative that aims to find out the names, dates and tribal affiliations of all people who attended boarding school,” she said. “…It would not only help in the healing, but allow (tribal people) a place to come and do research to find out about their families. It also would be very helpful to us in filling in the holes we have in the records.”

Volunteers cleaned up site

Researchers have located some of the documents related to the school housed at the San Bruno National Archives in California. In 2007, the Nevada Department of Transportation initiated the Old Stewart Indian Cemetery Clean-up Project, an effort that involved the Washoe Tribe, the Nevada Indian Commission, the Virginia City Cemetery Foundation and the Stewart Indian Colony Youth Group. The young volunteers cleaned up the site, repaired broken grave markers, and documented more than 250 gravesites. Researchers pored through federal records, copies of the school newspaper, obituaries, death certificates and other sources to find out more about the people who rest there.

Some of the results of that research are listed on the Find a Grave website, where 176 Stewart cemetery graves are catalogued. The people interred beneath those markers were students who died while enrolled at the school, staff members, alumni, and their relatives. About half of those buried in the 176 plots listed on Find a Grave were adults, the rest were children, including some infants.

Students who died at the school also are buried in other cemeteries around Northern Nevada.

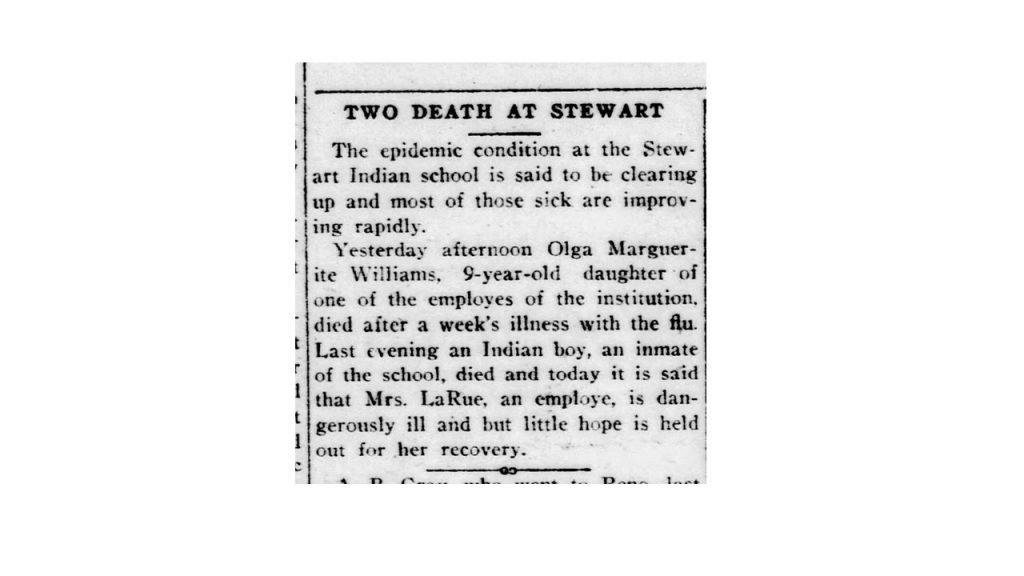

Nevada Appeal, March 26, 1919

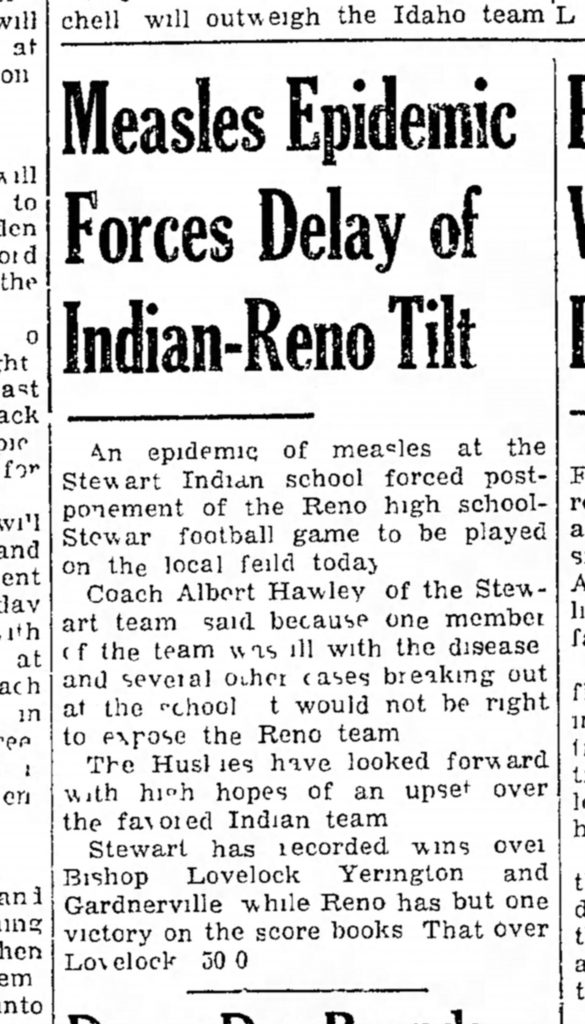

Reno Evening Gazette, Nov. 23, 1935

Epidemics and outbreaks

Those researching the names on the Old Stewart Cemetery markers found evidence documenting students who died of communicable diseases, which spread easily in the close conditions at the institution.

Other deaths are connected to epidemics. In 1896, for example, four children between the ages of 7 and 13 were interred there. Researchers attributed some of those deaths to the “Russian flu.” In 1919, four children between the ages of 12 and 15 were buried in the cemetery. Newspapers at the time reported that a total of five children and three staff members died in the third wave of the Spanish flu pandemic.

A similar spike in burials occurred in 1906, when five children ranging in age from 7 to 10, and a 21-year-old male student were interred, but researchers found no connection to a disease outbreak at the school that year.

The public summary of the clean-up project notes the existence of unmarked graves in the cemetery, but no number is noted. More detailed information, including a digitized map of gravesites, is in the custody of the Washoe Tribe. The tribe created an on-line virtual “cemetery,” where relatives can share photographs, stories and information about their loved ones.

Scientific racism

When the school opened in a single wooden building 1890, it had no medical facilities. During the first half century of its history, tuberculosis and trachoma (an eye infection than can result in blindness) were endemic at the school. Epidemics swept through the student body and outbreaks of illnesses, including measles, mumps and related infections, were common.

Bonnie Thompson wrote her doctoral thesis about the school and the evolution of its policies on student health in 2013, while a student at Arizona State University. Thompson wrote that the school opened during an era of scientific racism, which continued through 1905.

“Medical officials and the Indian Office largely believed that Indians’ ‘savage’ lifestyle and traditional beliefs predisposed them to chronic diseases… Following this logic, the Indian Office did little to prevent students from contracting these diseases or other illnesses other than isolating contagious students.”

— Bonnie Thompson, doctoral thesis, 2013.

An infirmary was built on campus in 1905 and a full-time nurse joined the school staff. Germ theory eventually took hold, but the consistency of better nutrition, good sanitation and the best-available health practices varied over the years.

“Mumps, scabies, impetigo, measles, smallpox, and influenza all reached epidemic proportions at Stewart between 1890 and 1940,” Thompson wrote. “…The sheer magnitude of these epidemics struck fear into the children and their parents and reinforced the idea that boarding schools were death traps.”

Sent home to die

A sanatorium for students infected with tuberculosis was built in 1916, but it was always inadequate for the demand. Often, critically ill children were sent home.

“To avoid deaths at the school, the sanatorium also sent home students with advanced tuberculosis as soon as possible,” Thompson wrote. “The wishes of parents and children certainly played a role in the students’ return to their families. Parents wanted to say goodbye to their children before they died. But by sending the children home, the school pushed its responsibility for sickness and the cost of further care onto other Indian agencies and families themselves.”

Superintendents only reported deaths that occurred on campus, several researchers noted.

The ‘Indian New Deal’

In 1928, the federal Meriam Report laid bare the problems at Indian boarding schools, including the dismal states of nutrition and health care. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, dubbed the “Indian New Deal,” resulted in tribes using their new political power to pressure the federal Indian Office to reform its policies.

Stewart stepped up its education and prevention programs, but budget constraints and changes in leadership got in the way of implementing best practices. “Pupils at Stewart often complained about the quality and quantity of food, physical exhaustion from their work regimen, and crowded dormitories where they often slept two to a bed,” Thompson wrote.

Finding more records may provide more insight into how children lived – and died – at Stewart Indian School, but some gaps in the narrative may never be filled.

Numbers, not names

Nicholas Jackson, a graduate student in education at the University of Nevada, Reno, wrote his 1969 master’s thesis about the history of Stewart. He noted that quantifying the number of children who died of disease at Stewart, or at any federal boarding school, can be challenging.

“On an institutional level, superintendents reported deaths of nameless students in their annual reports to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs,” Jackson wrote. “Even then, no complete record exists and the rates of morbidity and mortality have to be pieced together from reports, letters, death certificates, student records, and grave stones.”

That’s part of what the federal review is trying to accomplish. The results may not be comprehensive, but any further information will shed more light on the experiences of the children who attended the school for generations.

Dedicated to the task

Filling in those gaps in the school’s history “looks like the direction the Secretary of the Interior wants us to take and that’s what we want to do,” Montooth said. Even if it’s possible to identify every student who was enrolled, many of their fates may remain unknown.

“If they were here and didn’t come back, you may not know why they didn’t come back,” she said. “Did they run away, make it home, and were able to hide (from the truant officer)? Did they not come back because they perished? It’s such a complex situation. Most of the alumni and staff records we have specific to the school indicate that there wasn’t a big focus on record-keeping here. It followed that if the operation was violent, and would reflect poorly on the federal government, then the folks who had the ability to keep those records wouldn’t have made that a priority.”

Still, Montooth said, every effort will be made to

learn as much as possible. “We want to be transparent and to be able to

tell relatives that, yes, this is when your relatives went to this

school and this is what we now know about them.” SOURCE

No comments:

Post a Comment