✊🏽✊🏽✊🏽

Watch @aliciakeys use her platform to speak up for Native rights as she accepts the Ambassador of Conscience Award: pic.twitter.com/KTakWxNGRK— Fusion (@Fusion) May 31, 2017

✊🏽✊🏽✊🏽

Watch @aliciakeys use her platform to speak up for Native rights as she accepts the Ambassador of Conscience Award: pic.twitter.com/KTakWxNGRK— Fusion (@Fusion) May 31, 2017

READ: https://splitfeathers.blogspot.com/2016/07/toxic-stress-ace-study-violence-trauma.htmlUse the search bar on this blog for more about the ACE study.

President

Trump’s plan to review and possibly reverse his predecessor’s

protection of a wild swath of Utah threatens Indian sovereignty.

President

Trump’s plan to review and possibly reverse his predecessor’s

protection of a wild swath of Utah threatens Indian sovereignty.

“My mother, who was 80 per cent native, warned us never to tell anyone we were Indians,” she says. The reason was heartbreaking: Long before Paulette and and her siblings were born, her mother had two children who were taken from her by authorities and put up for adoption.“She never saw them again, and she never, ever got over it,” says Steeves. “Because of that, it was really important to her to hide our Indian-ness.”

The National Indigenous Survivors of Child Welfare Network is pleased to announce the launch of our new logo and... https://t.co/RAcPPcSqMc— Bill Stewart (@liamissa) May 1, 2017

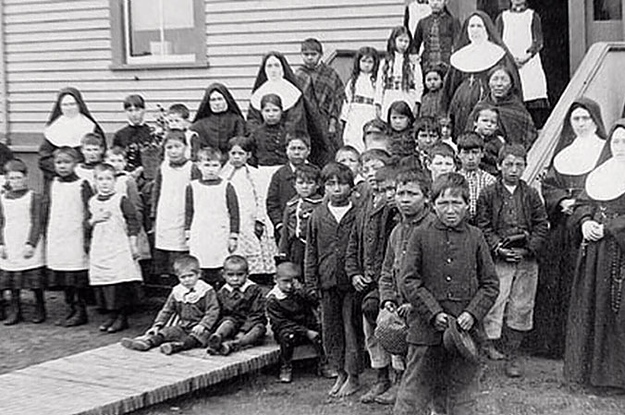

“The

profound impacts of residential schools are still rippling through our

communities today and will continue for generations to come.”

“The

profound impacts of residential schools are still rippling through our

communities today and will continue for generations to come.”

GO TO: https://blog.americanindianadoptees.com/ for updates and news. THIS BLOG cannot be updated...